The Future Used to Be Better

How We Lost Our Belief in Progress

A Dutch artist friend of mine, Daan Samson, has created a series of installations he calls “prosperity biotopes”. Though executed in various mediums, they share a unifying theme: the harmony of pristine nature and cutting-edge technology. At his exhibition in Amsterdam, I spotted ants scuttling on an ant plant alongside a sleek steel Nespresso milk frother, its presence as enigmatic as the black monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

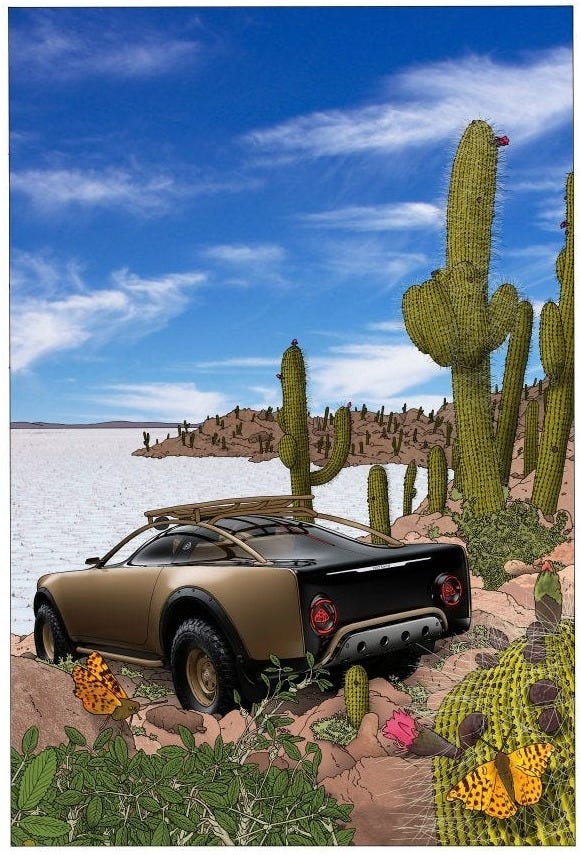

Then there was this drawing on the wall showing a shiny electric dream car from Mercedes-Benz, parked on a Bolivian salt flat and flanked by sturdy cacti.

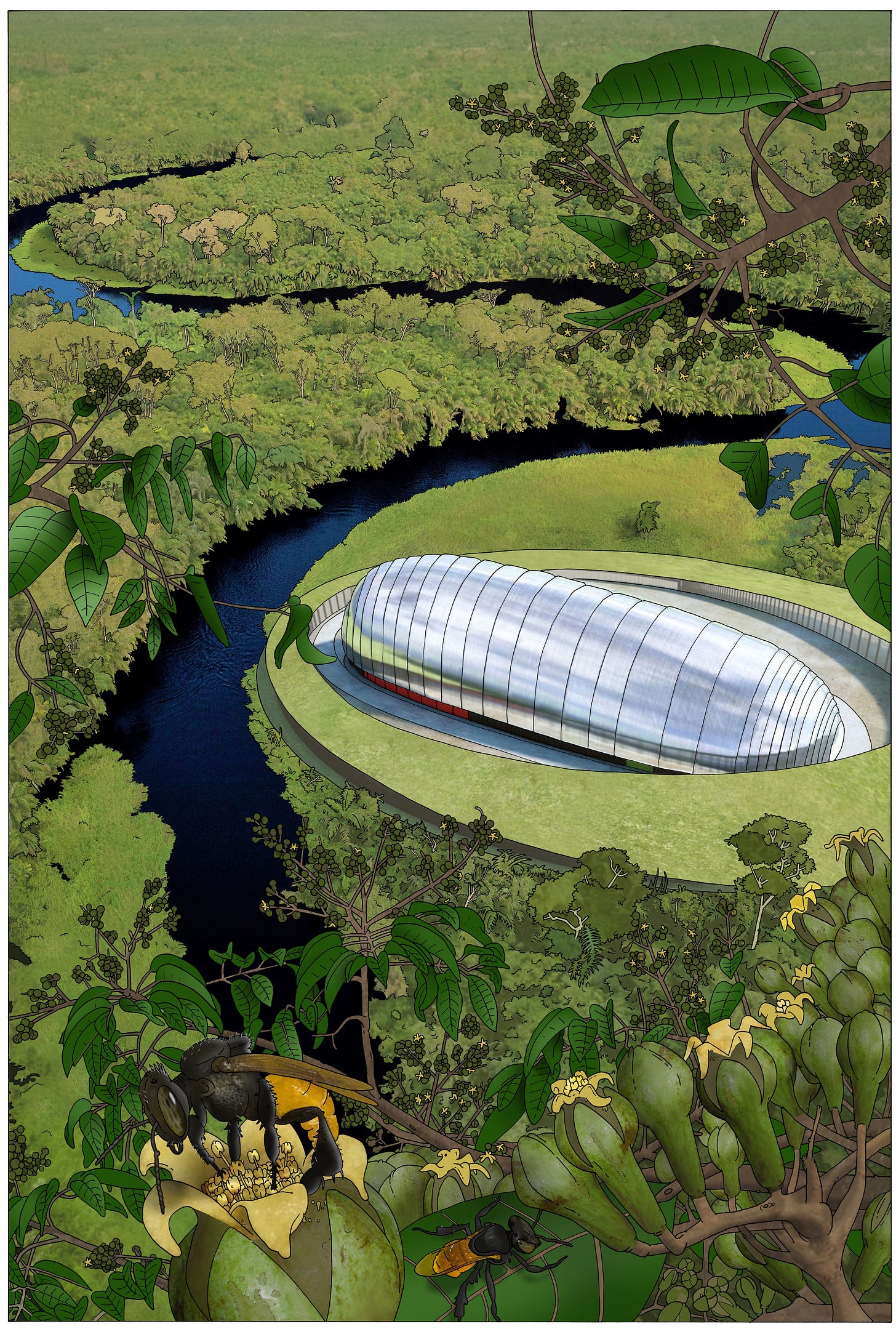

As an unabashed nuclear bro, I have to say my favorite prosperity biotope featured a futuristic small modular reactor (SMR) by Rolls-Royce, nestled deep in the Congo Basin rainforest. Its sleek, hulking form resembles a steel caterpillar, glistening scales half-buried in the earth, like a metallic version of Frank Herbert’s giant sandworms in Dune. It’s the kind of utopian vision ecomodernists love: high-density technology surrounded by untouched natural beauty.

By fusing the natural and the artificial, Samson invites us to think about the relationship between civilization and wilderness. Must we choose between the splendor of wild nature and the marvels of cutting-edge technology, between majestic redwoods and soaring skyscrapers? Or is it possible to have our cake and eat it too?

Even more striking than Samson’s prosperity biotopes were the reactions from the art world. Some curators and art critics assumed his art had to be ironic and subversive. Was he slyly mocking our consumer culture and its tacky product placement? Or was he calling out the encroachment of technology on Mother Nature? And wasn’t there a hint of capitalism critique beneath the surface? Art experts couldn’t wrap their heads around the notion that Samson’s work carried a sincere, non-ironic message: we don’t have to choose between nature and comfort—we can totally have both.

When Samson applied for subsidies from the city of Rotterdam, he got an unintentionally hilarious response. The city’s cultural committee had decided that his art project was “preposterous.” Why? They felt that the artworks “lacked critical reflection” and would have much preferred a “socially critical perspective on welfare.” Loosely translated: if you want to make art in a 21st-century European welfare state, your work better attack modern welfare, technology, and consumerism. And if you’re hoping to snag some government subsidies—milk from the capitalist cash cow—then you’d better declare yourself an enemy of capitalism.1 An insolent artist celebrating modern technology and consumption? No dosh for this buffoon!

What happened?

As a believer in progress, I’m loath to admit that anything was better in the past. After all, as the American journalist Franklin P. Adams once said, “Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.” But in recent years, I’ve reluctantly started to recognize that something has really changed for the worse. Pessimism and doom-mongering have always been with us, but over the past half century we seem to have completely soured on the idea of progress. Even so-called “progressives”, as I write in my book The Betrayal of Enlightenment, have turned their backs on progress. Socialists like Karl Marx and Sylvia Pankhurst dreamed of a world of abundance for all and infinite growth, celebrating plentiful energy and denouncing the scarcity mindset. By contrast, many progressives today warn that economic growth is a dangerous fetish, that “technofixes” won’t save the climate, and that the best energy is the “energy not consumed.”2

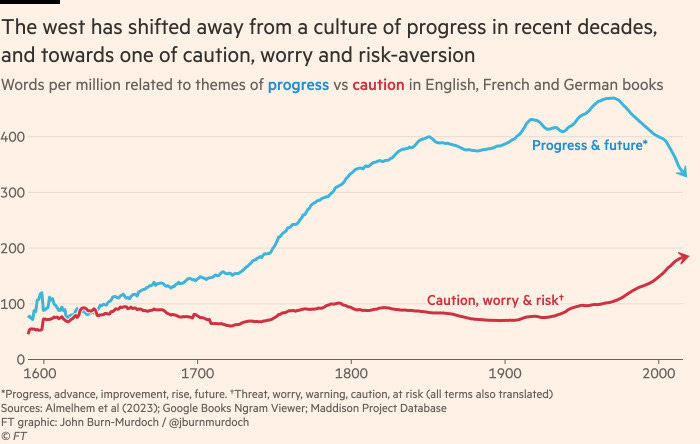

Plotting the evolution of the Zeitgeist is no easy task, but

from the has recently made a valiant effort. If we look at the frequency of terms related to progress, improvement and the future over time, we see a decline by about 25% since the 1960s, while “those related to threats, risks and worries have become several times more common”.And indeed, the arts seem to reflect this waning belief in progress. If you dive into the art and popular culture of the past, it seems our ancestors were genuinely more optimistic about the future and more confident in modernity. At least our recent ancestors—because belief in progress is itself a recent invention.

How belief in progress started

The belief in progress started to take shape in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards, when the steady accumulation of knowledge and innovation first became noticeable within the span of a single generation. For the first time, history felt like an arrow pointing forward: new innovations built on the old ones, and the old ones were never lost again. This naturally raised the question: how much better could the future be?

Dreams of paradise were not new, but they had usually been imagined as a golden age in the distant past. Now, for the first time, people began to believe that human ingenuity itself could create a perfect—or at least vastly better—society in the future. If human knowledge continues to expand, our descendants will surely live in a world of abundant prosperity, freedom, and beauty. The first futurists were, not coincidentally, also pioneers of the scientific revolution. In his 1626 book New Atlantis, published posthumously, the English philosopher Francis Bacon describes a society on the fictional island of Bensalem in the Pacific Ocean. The harmonious community on this island is centered around the House of Solomon—a kind of research institution dedicated to investigating the world to obtain useful knowledge that can improve the lives of its inhabitants. The Bensalem islanders excel in “generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit.”3

When Bacon wrote New Atlantis, a society of abundance and unlimited freedom was still only a distant dream—a promissory note grounded in philosophical first principles. With the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, however, ordinary people began to enjoy the fruits of progress. For the first time in history, living conditions improved noticeably within the span of a single lifetime. Before long, there was a whole cottage industry of utopian novels, envisioning futures of technological perfection, abundance, and universal brotherhood or sisterhood. The most popular title in that genre was Looking Backward by the American writer Edward Bellamy, published in 1888. The main character falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes up 113 years later, in the year 2000, to find the society of his dreams. No one has to work anymore, everything is free, and hunger and poverty have been eradicated. 19th-century Europeans were thrilled: Bellamy’s utopian novel became one of the best-selling books of the century.

The poetry of progress

Have you ever read poetry singing the praise of industrial machines? It sounds quaint today, but was quite common in the past, as

from has documented. The eighteenth-century poet and Enlightenment thinker Erasmus Darwin—grandfather of Charles—wrote epic poems in tribute to steam engines, grain mills, and blast furnaces. Darwin senior even predicted the invention of locomotives and airplanes—and was quite chuffed about the prospect. In the 19th century, Rudyard Kipling wrote an ode to the steamboat, likening its mighty machines to a symphonic orchestra. Walt Whitman gushed about railroads, canals, telegraph cables, and praised their “noble inventors”. Here are the bracing first lines of his Passage to India:Singing my days,

Singing the great achievements of the present,

Singing the strong light works of engineers,

Our modern wonders, (the antique ponderous Seven outvied)

In the Old World the east the Suez canal,

The New by its mighty railroad spann’d,

The seas inlaid with eloquent gentle wires;

Likewise, painters often depicted industrial machines—furnaces, mills, iron forges, coal mines—in a positive light. Rather than appearing dark or foreboding, they are shown as heroic and noble, sometimes even in harmony with their surroundings.

And why indeed shouldn’t there be beauty in technology, in using our wits to improve the human condition? “Poetical,” wrote the British journalist and philosopher G.K. Chesterton in 1908, are “things going right.”

The most poetical thing, more poetical than the flowers, more poetical than the stars—the most poetical thing in the world is not being sick.

This upbeat spirit persisted well into the 20th century. Some readers might still have childhood memories of it. In the visual arts, you had movements like Art Deco and Futurism, which glorified industrial machines, assembly lines, and monumental skyscrapers. Or a movement like Pop Art, which celebrated mass production and consumerism.

The 19th century and the first half of the 20th century were also the heyday of World Fairs, or Universal Exhibitions, which celebrated technological innovation with an optimistic eye toward the future. Millions flocked to these fairs to marvel at the latest inventions and share in the excitement of human ingenuity. Even in the 1930s, when dark clouds gathered over the world, the World Fairs in Chicago and New York still projected hopeful visions of the future. In 1933, the exhibition in Chicago was dubbed A Century of Progress, with the tagline: “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms.”

In New York in 1939, visitors left the fair sporting cheerful blue-and-white pins on their shirts that read, “I have seen the future,” apparently without feeling ridiculous.

Postwar progress

Even after the Second World War, that sense of optimism rebounded quickly. In 1955, Walt Disney opened his theme park Tomorrowland with these stirring words:

Tomorrow can be a wonderful age. Our scientists today are opening the doors of the Space Age to achievements that will benefit our children and generations to come. The Tomorrowland attractions have been designed to give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future.

The 1960s is probably the last decade when optimistic visions of the future dominated popular culture. In the high-tech future of the iconic TV series Star Trek, which first aired in 1966, problems on Earth like poverty and war had been solved for good, making them unsuitable for plot material. The storylines in the original Star Trek seasons are mainly driven by curiosity and a thirst for adventure, with the universe as an endless new frontier beckoning intrepid space travelers. As the famous tagline of the starship Enterprise puts it: “To boldly go where no man has gone before!” Star Trek exudes the prevailing belief of the time in a bright future and a positive attitude toward technology.

In the same decade, millions of people tuned into The Jetsons, a futuristic TV series where folks zip around in flying cars and float on hovering platforms. Work was a thing of the past, every family had a robot housekeeper, and if you were hungry, you just pressed a button for a delicious meal! In 1967, CBS aired The 21st Century, a series where the iconic news anchor Walter Cronkite takes viewers on a tour of a twenty-first-century home. We see shiny kitchen robots, devices for medical self-diagnosis, and picture phones for video conversations. (Moral progress proceeded at a somewhat slower pace, as women were still confined to the kitchen.)

Newspaper ads from electric utility companies promised a “higher standard of living” tomorrow, all thanks to abundant power generation. Soon, we’d be gliding through the skies on “flying carpets,” powered by batteries. Just hop on, push a button, and off you go—no more parking problems! “They’re working on it,” the ad boasted. In a 1966 New York Times article titled “A Glimpse of the Twenty-First Century,” leading scientists predicted a world without deserts, dirty smog, or industrial noise. The human population was expected to swell to 25 to 50 billion, living in unprecedented luxury thanks to nuclear power and other futuristic technologies. Incredibly, this tenfold increase in global population was seen as a hopeful vision, not the impending catastrophe that later environmentalists would make it out to be. Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey, also captured that belief in the uplifting power of modern technology. Sure, the spaceship’s computer, HAL-9000, goes haywire and tries to kill off the crew, but in the end human intellect prevails.

When the future looked bright

This positive attitude towards technology and unbounded optimism about the future seems very alien today. When Donald Fagen from Steely Dan sang about that radiant optimism of the post-war era on his 1982 album The Nightfly, it already sounded nostalgic. In his song about the ‘International Geophysical Year’ (1957), Fagen reminisces about the good old days when the future seemed to be glorious and free, thanks to the advancement of science and technology:

The future looks bright

On that train all graphite and glitter

Undersea by rail

90 minutes from New York to Paris

What a beautiful world this will be

What a glorious time to be free, oh

To a twenty-first-century observer, the future no longer appears so “glorious.” Stories of a bright tomorrow powered by technological progress are often dismissed as, at best, naive—or, at worst, as the self-serving utopias of Silicon Valley moguls seeking only to enrich themselves.

Earlier inventors like Samuel Morse or Thomas Edison were hailed as cultural heroes. Today, figures like Sam Altman or Bill Gates are more often met with suspicion or outright hostility. Whenever some new technology like GPT arrives on the scene, most people can only fret over the horrors that lie ahead: an explosion of deepfakes and misinformation, the disappearance of human relationships, the demise of intelligence and of human civilization, or even humanity’s enslavement by predatory robots. When Jonas Salk discovered a vaccine against polio in 1955, people poured into the streets and hugged strangers in joyous celebration. Bells rang across America, factories closed, and parades were held. But who among us danced in the streets in November 2020, when Pfizer announced its highly effective COVID-19 vaccine—a breakthrough that would save 20 million lives within a year?

Depictions of the future in popular movies and TV series are like a tale of a thousand-and-one nightmares. If we’re not wiped out by AI, then maybe it’ll be those predatory aliens. If nuclear war isn’t laying waste to the planet, then climate catastrophe will finish the job. And if, by some miracle, a few of us survive all this mayhem, we’ll probably wake up in a totalitarian hellscape—either trapped in a world of miserable enslavement (the tradition of Orwell’s 1984) or stuck in a soulless, hedonic culture where every desire is fulfilled with a pill or the push of a button (Brave New World’s tradition).

Here are just some of the most influential examples. In Blade Runner, the future is a smog-choked and polluted hellscape, where technological progress has created a dehumanizing society dominated by mega corporations. In The Hunger Games, a totalitarian world government forces people to fight to the death in sports arenas by way of entertainment. In The Matrix, a race of super-intelligent robots have enslaved humans as living batteries. In The Handmaid’s Tale, women are enslaved as breeding machines under a fundamentalist Christian theocracy.

The sci-fi series Black Mirror is the most inventive, as it explores a completely different future in every episode. I should confess that I’m an apocaholic myself and big fan of the series. Who doesn’t like to be creeped out by dystopian visions now and then? Still, of the 27 episodes in the first six seasons, only one can truly be called utopian, with its straightforward happy ending (San Junipero, by far the best one in my opinion).4 All the other episodes are pure nightmare fuel, usually involving some novel technology—from virtual reality to killer drones, from brain chips to surveillance cameras.

The most “hopeful” future is one where we just avert some catastrophe or another. A great example is The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson, one of the most popular sci-fi novels of recent years about the threat of global warming. Robinson’s book stands out because, rare among climate novels, it has a happy ending of sorts. But don’t get too excited: the ending is “happy” only in the sense that we stave off total catastrophe —after tens of millions of climate deaths and a wave of gruesome eco-terrorist attacks—before finally resetting the planet to the so-called “stable” pre-industrial climate (which wasn’t stable at all).

And what about other art forms? Step into any museum of contemporary art and you’ll encounter a relentless litany against modern technology, the ravages of capitalism, and “consumerist culture” (otherwise known as prosperity). If we are to believe contemporary art, industrial capitalism produces every conceivable ailment: loneliness, alienation, commodification, mental stupefaction, spiritual emptiness, loss of authenticity. The diagnoses vary and often contradict one another: is modern man a docile herd animal, or a hyper-individualistic narcissist? Do we live in an emo-cracy reigned by feelings, or in a neoliberal order dominated by cold numbers and rational calculations? Positive appraisals of prosperity have become so rare, as my friend Daan Samson has discovered, that any artist celebrating progress is met with bewilderment or disbelief.

Yes, I know we should be careful to avoid the temptation to cherry-pick in this walk through modern history. Even in the glorious 19th century, as Jason Crawford admits, you could definitely find poems about the impending collapse of civilization and the horrors of the “dark satanic mills,” as the English poet William Blake famously described coal factories. Likewise, there was no shortage of technophobic art during the Golden Years after World War II, or critics who abhorred consumerism. And yet, I’m pretty sure that a century ago, an art committee would have been less shocked by Daan Samson’s cheerful odes to prosperity. As the Bavarian comedian Karl Valentin once said, “The future used to be better, too, in the old days.”

A self-fulfilling prophecy?

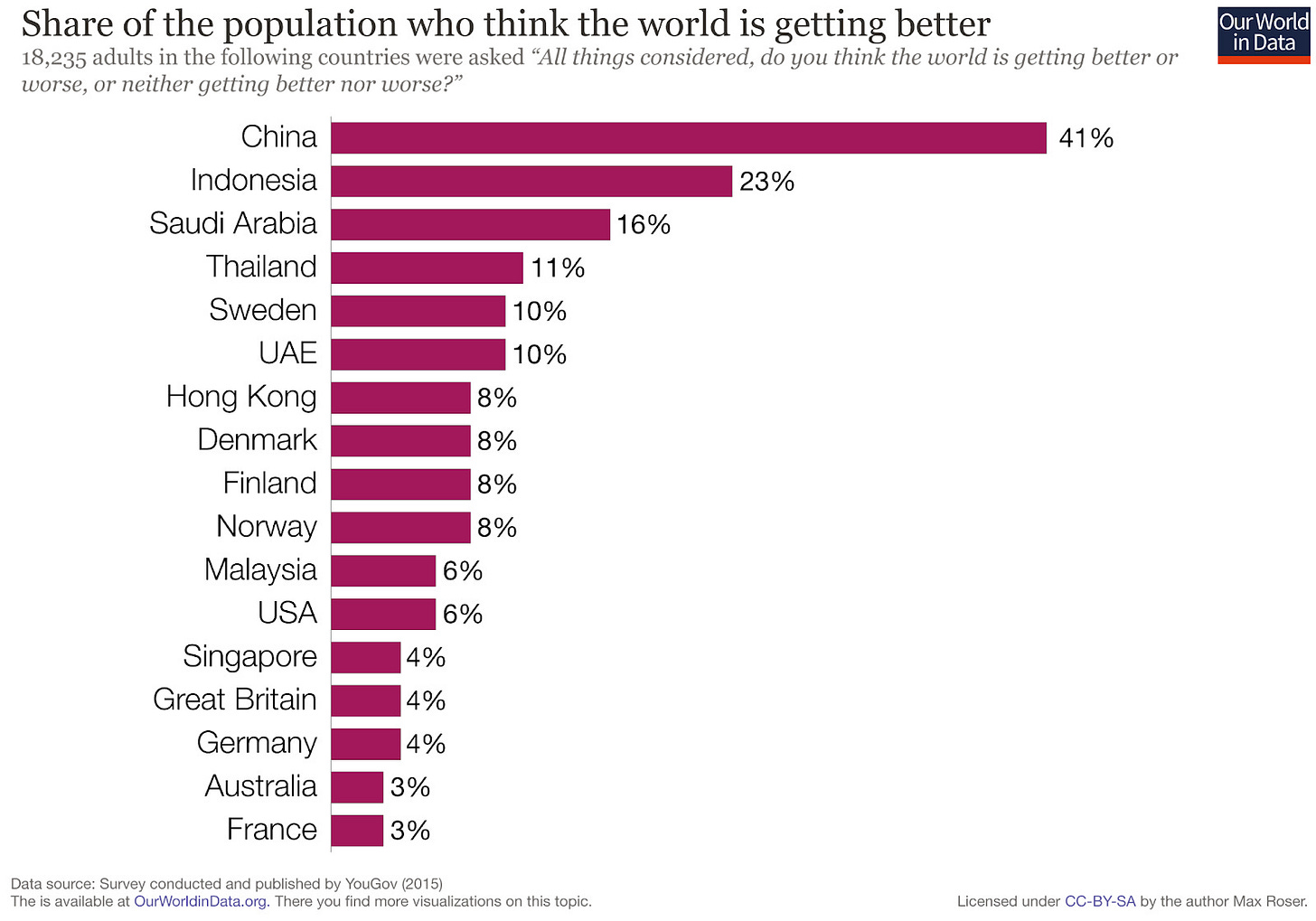

Losing faith in progress—and in ourselves—might come with dire consequences. Public surveys show something that should alarm anyone rooting for progress: in most Western democracies, less than 10% of people think the world is on the right track. What’s even more startling is that, in developing countries like China and Indonesia, the optimists make up a solid 41% and 23% of the population. A Pew survey from 2014 confirms that people in emerging economies are much more optimistic about the future of their children than in rich countries. John Burn-Murdoch’s graph above suggests that belief in progress was at similarly high levels in the West until half a century ago.

So, what happens to a civilization that gives up on its faith in progress? One theory is that we fall into the trap of a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the French-German polymath Albert Schweitzer once said: “Real progress is closely linked to the faith of a society who considers this progress possible.” It’s tough to measure the Zeitgeist over time, but if you just look at metrics like GDP growth, economic productivity, and innovation rates, you start to notice some pretty clear signs of stagnation. The economy is still growing, but it’s moving at a slower pace than in previous decades—especially in Europe. We’ve got more PhDs than ever, yet fewer groundbreaking discoveries.

If people lose their belief in progress and no longer see technological innovation as something worth striving for, then stagnation is what you’ll get. People will oppose new construction projects, governments will stop planning for rising energy consumption, companies will no longer invest in research and development— and art committees will snort at anyone who tells a positive story about technology and human prosperity.

Isn’t it time we renewed our faith in progress and innovation? To build a better world, we need not only scientists and inventors but also people like Daan Samson—artists who reveal the beauty and poetry of modern industrial technology and who dare to imagine even better futures. What kind of paradise might we wake up to in 2125, after another century of hypnotic slumber?

[This is a heavily revised version of a piece that was originally published at and in

’s TERRAFORM collection]As Joseph Schumpeter noted, in a capitalist society, openly denouncing capitalism is “almost a requirement of the etiquette of discussion.” See my essay about biting the hand that feeds you.

Progressives are of course not the only ones distrustful of technology. But it’s more surprising when such disdain for technological progress comes from progressives (what’s in a name?). As

generalized in a recent piece lamenting techno-phobia, “the right fears physical technologies, while the left fears digital technologies”. Conservatives distrust vaccines, lab-grown meat, and solar power, while progressives panic over self-driving cars, nuclear power, and AI. And both share a profound hatred for GMOs.If you want to be pedantic, Bacon’s book isn’t strictly about the future but about an ideal society in the present. Still, it describes a blueprint for a different and better society that we can bring into existence if we put our minds to it.

I haven’t finished the latest (seventh) season yet.

This is a fascinating cultural transformation. Right when a positive view of material progress seemed to have more evidence to back it up than ever before, cultural and academic elites turned against it.

I do not have a complete explanation for the pivot, but I think some important factors were:

1) The coming of age of the Baby Boomers: the first generation that could take a materially comfortable life for granted.

2) The rise of Post-Modern Left-of-Center ideologies, particularly among college-educated baby boomers. This was concentrated among academics, teachers, entertainers and artists.

3) The decline of traditional religion as a moral foundation, particularly among the group above. Post-Modern Left-of-Center ideologies essentially filled the role of religion in being a moral foundation for many people.

4) The fundamental conflict between the reality of material progress and the assumptions of those ideologies, so people felt a moral need to explain away material progress as either a bad thing or not important.

I do not think all of the above were inevitable, but they might be a negative side-effect of widespread affluence.

I wrote a short piece this week arguing that in recent decades progress has been sold (at least in Romania) as the result of sacrifice: the current generations need to sacrifice for a better future for the next ones. This discourse manifests itself especially in times of economic hardship and austerity measures. Which is more or less what we have seen in this part of the world since the early '80s. Therefore, we need to be more pragmatic as to what we define as progress and what portion of the population has access to it. Also: I did not dance when Pfizer announced their vaccines but I specifically chose that version of it because of its innovative character. As such, I understand people who were not ready to be 'early adopters' of a medical breakthrough and chose the 'tried and tested' options.