The Four Faces of Gloom: How the West Gave Up on Progress

(Or: Richer, Safer, Sadder)

In his provocative book Has the West Lost It?, the Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani points out a curious paradox. In many ways, the world has never been in better shape than today, especially in Western countries. People are living longer, healthier, and safer lives than ever before. Mahbubani credits these enormous improvements in the human condition to the global spread of Western ideas and practices like modern science, liberal democracy, and free markets: “The biggest gift the West gave the Rest was the power of reasoning.” 1

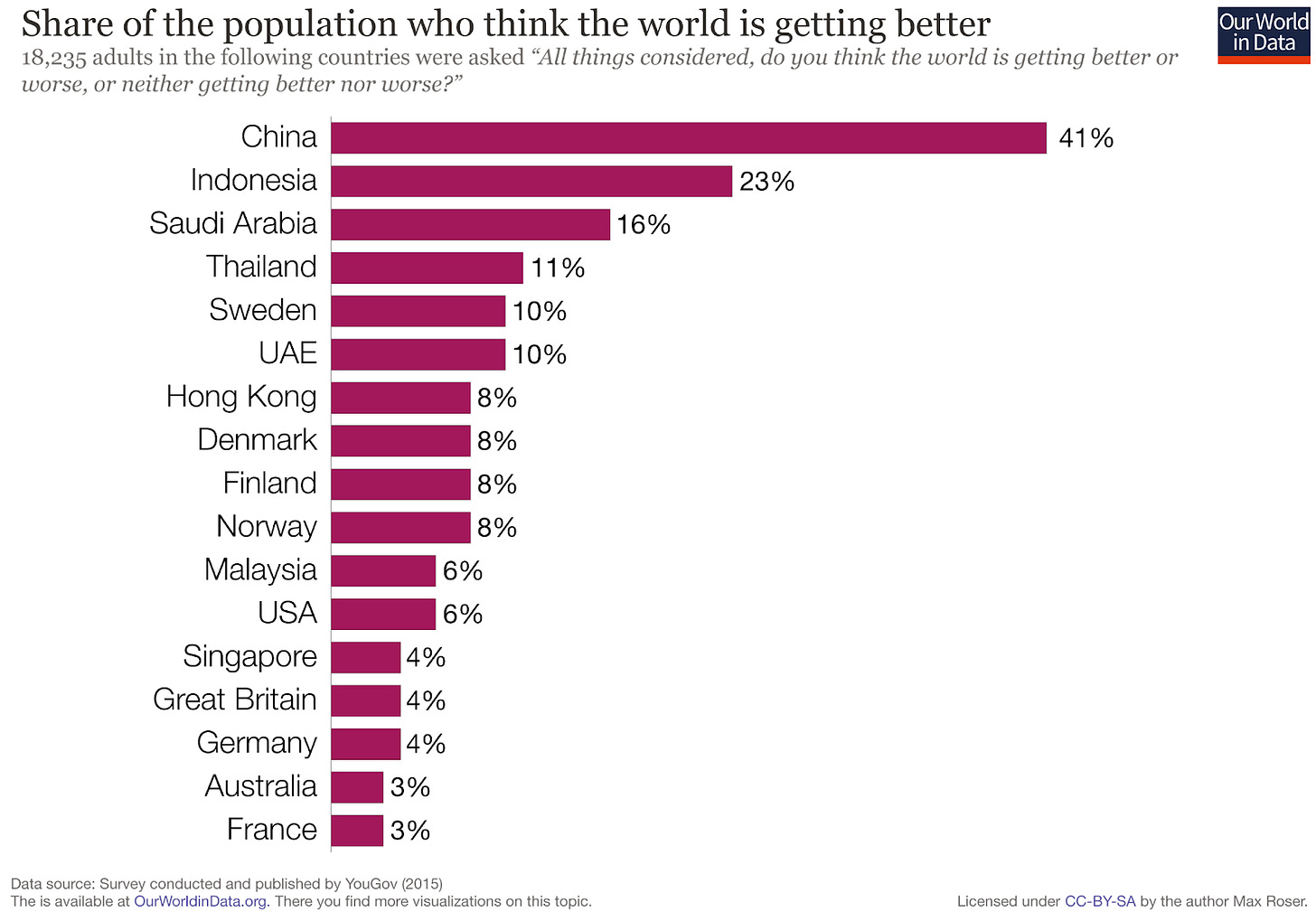

And yet, surveys show that nowhere are people more pessimistic about the state of the world than in the West. When asked if, all things considered, the world is “getting better or worse,” less than 10% of Westerners say it’s improving. In Western countries like France and Australia, that figure drops to a mere 3%. Meanwhile, in places like China and Indonesia, no less than 41% and 23% of people, respectively, believe the world is on the right track. Sure, this worldwide survey is a decade old already, but that makes it even more intriguing, considering that 2015 arguably looked somewhat more auspicious than today.

People in the West are depressed about a wide variety of things. Those on the Left are scared about global warming, collapsing ecosystems and rising inequality, while those on the Right worry about mass migration, a crisis of meaning, and Islamic fundamentalism, among other things. Most of all, the Left and Right are terrified of each other. For one camp, the Woke revolutionaries are tearing apart our Judeo-Christian civilization, while for the other, the right-wing populists are dismantling democracy. None of these worries are entirely made-up, and of course I won't try to tackle them all in one post.

What I want to do instead is provide a taxonomy of contemporary pessimism. Beyond their specific anxieties, we can identify four prototypes among the naysayers. While each group has a different view of human history, they all share a strong skepticism about the very notion of progress—the Enlightenment belief that we can keep making the world better and better. By analyzing these four types, we can uncover some surprising similarities among pessimists from widely different political backgrounds.

1. The Nostalgic Naysayer

Ah, the good old days—when everything was so much better! Back then, people were kinder to one another, we lived in harmony with nature, and life was rich with meaning. Different nostalgics locate their Golden Age in different eras. Some long for the days of their youth, while others reach further back to the Trente Glorieuses after the Second World War, the belle époque before the First World War, or even the tight-knit agrarian communities of the Middle Ages. Some take it all the way back to our hunter-gatherer days, when we still lived in harmony with nature and with each other.

Romanticizing the past is often seen as a hallmark of conservatism, but progressives are hardly immune. They just paint their ideal past with different shades. Right-wing nostalgics pine for the days when young people respected their elders and cherished cultural traditions, while their left-wing counterparts mourn the bygone eras of solidarity, shared commons and mutual trust. Even the famous left-wing anthropologist David Graeber, in his book The Dawn of Everything with David Wengrow, has portrayed the lives of hunter-gatherers as freer and richer than today.

The trouble with nostalgic pessimism is that eventually people start wondering how paradise was lost and who’s to blame for spoiling it. Before long, some scapegoat will be identified: maybe it’s the global elites, the bourgeoisie, the neoliberal Chicago boys, the cultural Marxists, or the invading Muslim hordes. Once upon a time our societies were idyllic, until “they” came along and ruined everything. In the days of yore we lived in harmony with Mother Nature, but then we started ravaging her with coal mines, dirty factories, concrete jungles, mechanized tractors and synthetic fertilizers.

If only we could rewind the clock and make XYZ great again! Exit polls in 2016 revealed that the best predictor of a Trump vote was plain old pessimism. Among those who thought life would be tougher for the next generation, 63 percent went for Trump, while just 31 percent sided with Hillary Clinton. As we’re witnessing today, this longing for the days when America was "Great" is anything but harmless. Nostalgia can fuel the fire for revolutionary upheaval—draining the swamp, tearing down the system, and blowing up the international order.

2. The “Just You Wait” Doomster

This breed of pessimist is willing to admit—unlike the Nostalgic Naysayer—that the world is much better than before. But, they will insist, it cannot possibly last. Pride cometh before a fall, after all. Our modern hubris and naïve belief in progress must face a reckoning sooner or later. I like to call this the “Just You Wait” school of pessimism. For now, everything might seem stable, but don’t be deceived. Soon we’ll cross some critical tipping point and then plunge into the abyss. This brand of pessimism often suffers from what the writer Matt Ridley has dubbed “turning-point-itis”—the belief that we’re living in a pivotal moment in history, and we’re just lucky enough to have front-row seats to the unfolding drama.

“Just You Wait” Doomsters can be found all across the ideological spectrum, but they tend to catastrophize about different issues. In Europe, runaway climate change and mass migration are the top contenders for filling people’s heads with dread. If you were to draw Venn diagrams of these two types of doomers, however, you'd see hardly any overlap. The more someone fears one catastrophe, the less likely they are to fret about the other.

Right-wingers anxious about Muslim hordes landing on our shores often brush off worries about a climate collapse. If they acknowledge human-driven global warming at all, they dismiss climate activists as “eco-doomers” and “hysterics.” On the flip side, climate catastrophists tend to wave away fears of Islamization through mass migration, viewing them as paranoid fantasies concocted by Islamophobic bigots.

The trouble with “Just You Wait” pessimism is that it can push otherwise reasonable people to take drastic actions that end up causing far more harm than the problems they aim to solve. If you believe that the planet is going to hell in a handcart unless we dramatically change course, it might seem logical to endorse extreme measures you wouldn’t normally consider, like sabotaging energy development in poor countries. The climate catastrophist Michael Mann said the quiet part out loud when he wrote that: “we can't let them [poor countries] make the same mistakes we made—our climate can't afford it.” Bad people can do bad things, but an apocalyptic mindset can lead even decent people down a dark path.

Likewise, far-right politicians like the Dutch Geert Wilders who harbor grim visions of “Eurabia”—a Europe under Islamic rule—have openly called for banning mosques and cracking down on Muslim communities. The reasoning is eerily similar: we are in the midst of an emergency, so we must violate some of our freedoms now to avert their utter destruction later on.

At its most extreme, catastrophism can inspire terrorism. Take Ted Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber. In his manifesto Technological Slavery, he argued that dismantling modern technological civilization, though it would unleash lots of chaos, would still be less disastrous than letting it persist. Similarly, right-wing terrorists like Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant have used the warped logic of catastrophism to justify their horrific deeds, pointing to the “suicidal humanism” of European liberals or the alarmingly low birth rates of Westerners.

In this sense, "Just You Wait" doomerism is like the dark twin of utopian thinking. Instead of envisioning a perfect world, it sees an all-consuming disaster on the horizon. Both mindsets are dangerous for the same reason—they set up a utilitarian calculus with stakes that are infinitely high. In 2018, German historian Philipp Blom published What is at Stake?, a deeply pessimistic examination of the looming climate catastrophe. In the book’s final line, Blom drives his point home by answering his own titular question with one chilling word: “What is at stake? Everything.”

Paradoxically, the sky-high stakes of "Just You Wait" catastrophism can also lead to the opposite outcome—paralysis. If we’re hurtling towards the End of the World without any chance of taking the drastic measures needed to avert it, then we may as well surrender to the inevitable. French sociologist Bruno Latour, who transitioned from a postmodern critic of science to a climate doomer later in his life, sounds this note of despair in his book Down to Earth: The war is over, and we have lost it. If that's the case, why not just burn through the remaining coal and enjoy the party while it lasts?

Here again, such defeatism has a counterpart among the anti-immigration doomers. Some believe that the demography of Western Europe is so bleak that we should abandon ship and head east to countries like Hungary, the last bulwark against the rising tide of Islamization.

3. The Cyclical Pessimist

This kind of pessimist will concede that things are going pretty well for now, but insist that such spells of prosperity and peace have occurred many times in history, and have always fizzled out sooner or later. For the Cyclical Pessimist, history's path is as predictable as the changing seasons. Sure, the world might be getting better today (though most Westerners would demur), but don’t be fooled. It’s just a temporary upswing before the inevitable decline.

The poster child for this mindset is the German historian Oswald Spengler. In his 1918 opus, The Decline of the West, Spengler likened civilizations to living organisms—they grow, mature, wither, and die. Just as we can’t escape our own mortality, there’s no escaping the churning forces of history. According to Spengler, a typical civilization has a lifespan of a few millennia. By the early 20th century, he argued, Western civilization was on the cusp of its winter—its final chapter before the unavoidable end.

Spengler primarily focused on cultural and spiritual forces, but the idea of cyclical patterns extends to economics as well. In The Invisible Hand?, economic historian Bas van Bavel takes us on a journey through past golden ages—from the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad to the Dutch Golden Age in the seventeenth century. Market economies, he argues, rise and fall according to unyielding laws of economic history, collapsing under the weight of their own internal contradictions. This naturally leads him to a rather grim forecast about the future of our own economic system. According to Van Bavel, the early signs of decline—like the growing concentration of wealth—are already starting to show.

The problem with this cyclical narrative is that, when it comes to material prosperity and peace, none of those past golden ages can hold a candle to what we're enjoying today. Granted, progress is not guaranteed to continue indefinitely, but this cyclical mindset can easily slide into a cynical one. If all those upward curves are destined to come crashing down eventually, it’s tempting to feel like there’s no point in trying to change the inevitable.

4. The Treadmill Thinker

The Treadmill Thinker recognizes some objective measures of progress—more wealth, less violence, longer lifespans— but insists that we've missed the mark where it really counts. Much like Alice and the Red Queen in Alice Through the Looking-Glass, we’re running ourselves ragged only to find that, once we catch our breath, we’re still right back where we started.

A classic example of this treadmill thinking is the Easterlin paradox, named after economist Richard Easterlin. Back in the 1970s, he noted that people in wealthy countries didn’t seem any happier than those in poorer ones, and happiness levels in the West had remained pretty stagnant for decades. If that were the case, all our efforts to lift humanity out of misery would seem utterly futile.

In fact, we now know that the Easterlin paradox doesn’t exist. A slew of later studies, armed with richer data sets and better metrics, have shown that wealth and happiness actually go hand in hand, both within and between countries—wealthy nations tend to be happier than poorer ones, and within a given country the super-rich are generally happier than the merely well-off.

Another area where Treadmill Thinking runs rampant is social justice movements. Activists often dismiss claims of moral progress as mere naïve triumphalism that perpetuates oppression and upholds the status quo. Such skepticism is often shielded from refutation by expanding the definition of moral evils like racism or sexism, or by clinging to a version of Freudian symptom substitution: if one form of evil vanishes, it will be swapped with another equally pernicious one. Sure, explicit and overt racism has been on the decline, they’ll say, but now we're facing institutional and implicit racism, which is even more insidious.

Some even throw around the term “cultural racism”, an oxymoron that reframes negative views about different cultures as racism. This mindset leads to what I’ve called the Law of Conservation of Outrage: regardless of how much progress society makes, the level of moral outrage always remains constant.

Just as with its cyclical cousin, treadmill pessimism can drain our motivation to build a better world. If racism and sexism are always bound to reappear in different guises or be replaced by other ills, we might as well throw in the towel. As Steven Pinker observed in Enlightenment Now, this would mean that “progressivism is a waste of time, having accomplished nothing after decades of struggle.”

Defeatism is also the natural corollary of belief in the Easterlin paradox. If all that wealth hasn’t made us any happier, why even bother trying to promote economic growth in poorer countries? Maybe wealthy Europeans should just tell those African boat migrants to turn back and steer clear of our prosperous shores, since they would be destined for unhappiness anyway. They might as well stay put and remain poor, which would be better for the planet to boot (see above).

Belief in progress—the continual improvement of the human condition through science and critical inquiry—emerged during the European Enlightenment, as Kishore Mahbubani reminds us. European philosophers of the 17th and 18th century were among the first to propose the bold notion that humanity’s problems are soluble and that we’re not condemned to a life of misery. This grand project started to pay off about a century later, starting in West Europe and then spreading across the globe. But this was far from inevitable—it required hard work and determination.

Pessimism is not just factually wrong, it also undermines our confidence in the potential for future progress. It goes without saying that we’re not living in the “best of all possible worlds,” as Dr. Pangloss famously proclaimed in Voltaire’s satirical novel Candide, but we may well be living in the best one so far. If we want to prove Dr. Pangloss wrong once again, creating even better worlds in the years to come, we need to lean on the tried-and-true methods of science, free inquiry, and democracy.

If Westerners are dropping the ball, Kishore Mahbubani warns, countries like China and India will gladly scoop it up. They'll be grateful for the "biggest gifts" of the European Enlightenment, but won't waste a second looking back at the fading giant left behind.

So when will Westerners regain their belief in progress?

[If you enjoyed this piece, feel free to like, share, or subscribe — it helps more people discover my work through the inscrutable algorithm].

This is a heavily rewritten and updated version of an essay I once wrote for Quillette, under the title ‘Four Flavors of Doom’

Superb article, Maarten!

Great piece! I think your four types of pessimist make sense. Very interesting!