Why Fallacies Don’t Exist

(except in textbooks)

Have you ever wondered why people believe the moon landing was faked, vaccines secretly poison us, and Mercury in retrograde can ruin your love life? Why does irrationality seem so pervasive? A popular answer, beloved by academics and educators alike, points to fallacies—certain types of arguments that are deeply flawed yet oddly seductive. Because people keep falling for these reasoning traps, they end up believing all sorts of crazy stuff. Still, the theory offers hope: if you memorize the classics—ad hominem, post hoc, straw man—you will inoculate yourself against them.

It’s a neat little story, and I used to believe it too. Not anymore. I’ve become a fallacy apostate.

Growing doubts

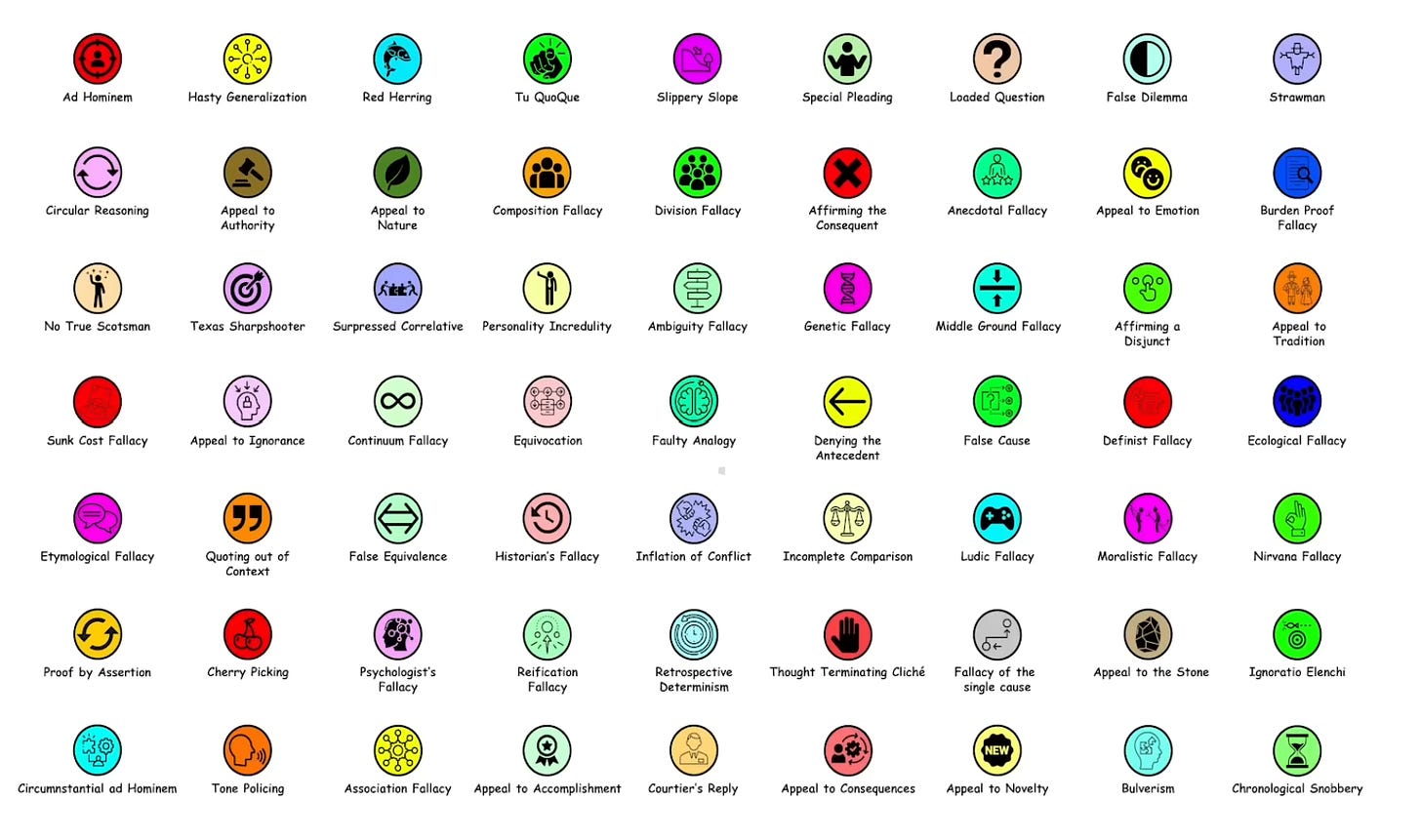

My doubts began when I was still in academia, teaching critical thinking to philosophy students and science majors alike. Fallacies are a favorite chapter in such courses. In some ways, they are ideal teaching material: they come in tidy lists and seem easy to apply. Many trace back to Aristotle and still parade under their Latin names—ad hominem, ad populum, ad ignorantiam, ad verecundiam (better known as the argument from authority), the slippery slope, affirming the consequent, and so on.

So I dutifully taught my students the standard laundry list and then challenged them to put theory into practice. Read a newspaper article, or watch a political debate—and spot the fallacies!

After a few years, I abandoned the assignment. The problem? My students turned paranoid. They began to see fallacies everywhere. Instead of engaging with the substance of an argument, they hurled labels and considered the job done. Worse, most of the “fallacies” they identified did not survive closer scrutiny.

It would be too easy to blame my students. When I tried the exercise myself, I had to admit that I mostly came away empty-handed. Clear-cut fallacies are surprisingly hard to find in real life. So what do you do if your professor tells you to hunt for fallacies and you can’t find any? You lower the bar. To satisfy the assignment, you expand your definition.

I turned to the classics to see whether I was missing something. The Demon-Haunted World by Carl Sagan is one of the most celebrated books on critical thinking and everyday irrationality. Like many works in the genre, it contains a dedicated section on fallacies, where Sagan dutifully lists the usual suspects. The curious thing, however, is that he rarely puts them to work in the rest of the book. The section feels almost perfunctory—as if, close to the deadline, Sagan’s editor had told him: “Shouldn’t you include a list of fallacies somewhere, Carl?” As in many textbooks, real-life examples are scarce. Instead, we get tidy, invented toy arguments that are easy to knock down.

Sagan is not alone in paying lip service to fallacy theory while making little real use of it. Here’s the most popular educational video on fallacies, with millions of views, which consists entirely of toy examples.

Or consider this recent viral TikTok video of a guy fighting with his girlfriend, racking up twelve logical fallacies in under two minutes. It’s an impressive performance—but obviously scripted. Another collection of toy examples, and not very persuasive ones at that.

All of this makes you wonder: if fallacies are as ubiquitous as we’re told, why is the theory always illustrated with invented toy examples?

The Fallacy Fork

Some time ago, I published a paper in the journal Argumentation with two colleagues (including my friend Massimo Pigliucci) arguing that fallacy theory should be abandoned. The paper is still regularly cited, and looking back I think it has aged pretty well (which can’t be said of all my old papers). I won’t bore you with the technical details, but since “fallacies” are constantly invoked in political debates, online and off, I thought it would be interesting to explain the core argument. Even if formal logic leaves you cold, you’ve probably seen how fallacy labels get tossed around in discussions. Maybe you’ve felt the frustration without quite being able to put your finger on it. Our paper tries to explain that irk.

Philosophers have attempted to define fallacies using formal argumentation schemes. The approach is appealing: it promises a systematic way to identify bad arguments across contexts. In practice, however, it proves remarkably difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Here is the crux: every so-called fallacy closely resembles forms of reasoning that are perfectly legitimate, depending on the context. In formal terms, good and bad arguments are often indistinguishable. Worse, there is almost always a continuum between strong and weak arguments. You cannot capture that gradient in a rigid formal scheme. As my friends Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber succinctly put it in The Enigma of Reason: “most if not all fallacies on the list are fallacious except when they are not.”

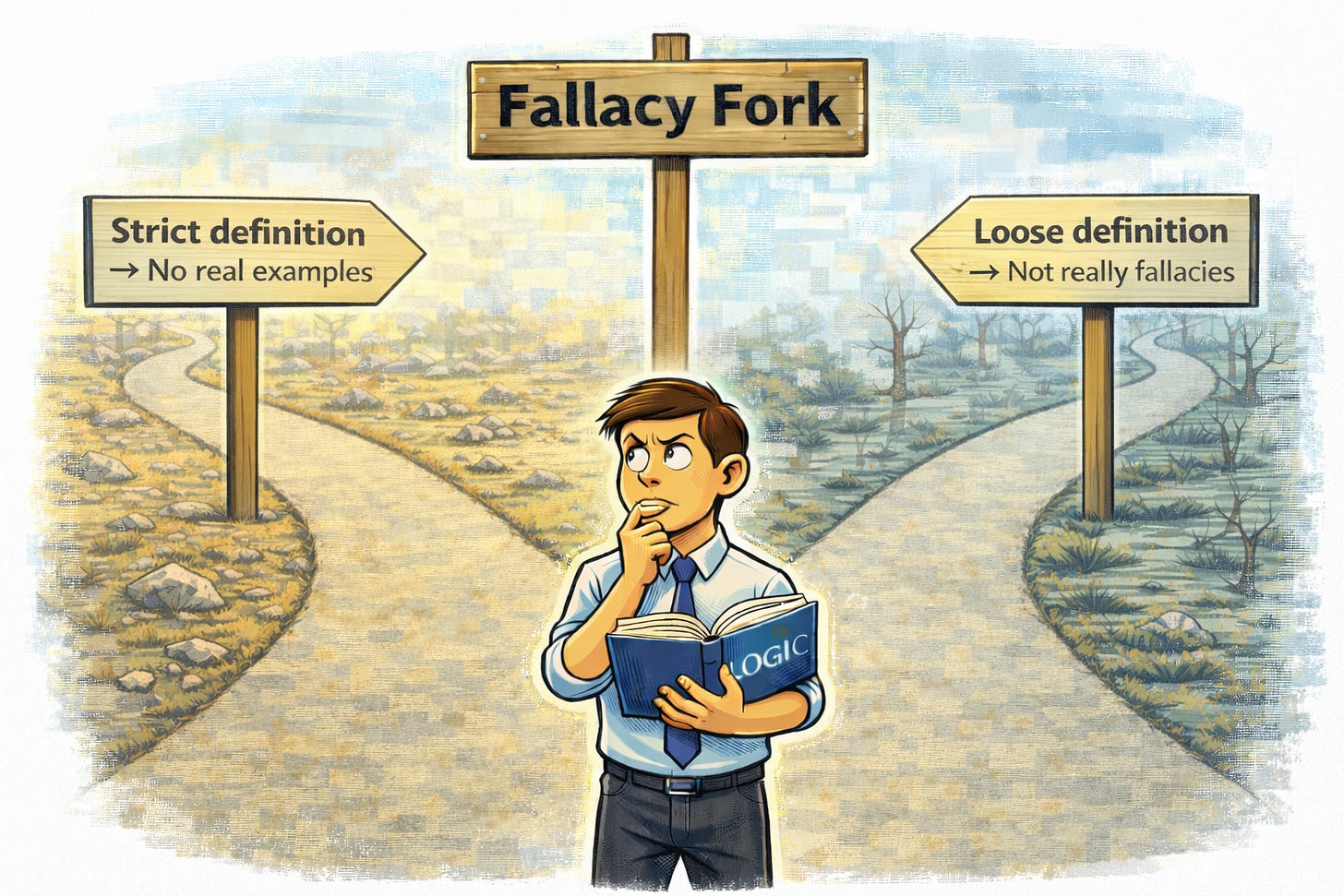

We show this by using what we call the Fallacy Fork. This destructive dilemma forces you to choose between two unpalatable options. First, I’ll lay out the two prongs of the dilemma. Then I’ll turn to some examples.

(A) You define your fallacy using a neat deductive argument scheme. In a valid deductive argument, the conclusion must follow inexorably from the premises. If the premises are true yet the conclusion could still be false, the argument is invalid—case closed. The trouble is that, in real life, you almost never encounter such clean, airtight blunders. You can invent textbook examples, sure, but flesh-and-blood cases are surprisingly rare.

(B) So you loosen things up and abandon the strict realm of deductive logic. You add some context and nuance. Now you can capture plenty of real-life arguments. Great. Except there’s a catch: once you relax the standard, your “fallacy” stops being fallacious. It turns into a perfectly ordinary move in everyday reasoning—sometimes weak, sometimes strong, but not obviously irrational.

Let’s see how some of the most famous fallacies fare when confronted with the Fallacy Fork.

Post hoc fallacy

As the saying goes: correlation does not imply causation. If you think otherwise, logic textbooks will tell you that you’re guilty of the fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc. You can formalize it like this:

If B follows A, then A is the cause of B.

Clearly, this is false. Any event B is preceded by countless other events. If I suddenly get a headache, which of the myriad preceding events should I blame? That I had cornflakes for breakfast? That I wore blue socks? That my neighbor wore blue socks?

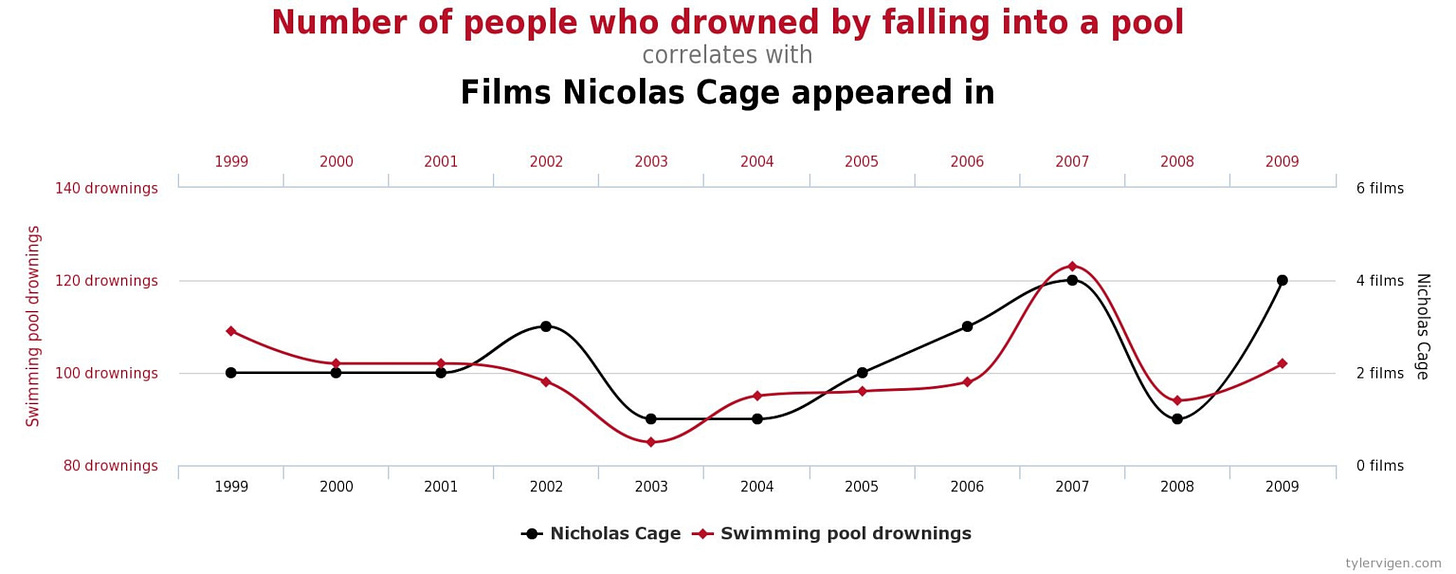

It’s easy to mock this fallacy—websites like Spurious Correlations offer graphs showing correlations between margarine consumption and divorce rates, or between the number of people who drowned by falling into a pool and the number of Nicholas Cage films released per year.

The problem is that not even the most superstitious person really believes that just because A happened before B, A must have caused B. Sure, in strict deductive terms, post hoc ergo propter hoc is a fallacy—but real-life examples are almost nonexistent. That’s the first prong of the Fallacy Fork.

So what do real-life post hoc arguments actually look like? More like this: “If B follows shortly after A, and there’s some plausible causal mechanism linking A and B, then A is probably the cause of B.” Many such arguments are entirely plausible—or at least not obviously wrong. Context is everything.

Imagine you eat some mushrooms you picked in the forest. Half an hour later, you feel nauseated, so you put two and two together: “Ugh. That must have been the mushrooms.” Are you committing a fallacy? Yes, says your logic textbook. No, says common sense—at least if your inference is meant to be probabilistic.

Here, the inference is actually reasonable, assuming a few tacit things:

Some mushrooms are toxic.

It’s easy for a layperson to mistake a poisonous mushroom for a harmless one.

Nausea is a common symptom of food poisoning.

You don’t normally feel nauseated.

If you want, you can even spell this out in probabilistic terms. Consider the last premise—the base rate. If you usually have a healthy stomach, the mushroom is the most likely culprit. If, on the other hand, you frequently suffer from gastrointestinal problems, the post hoc inference becomes much weaker.

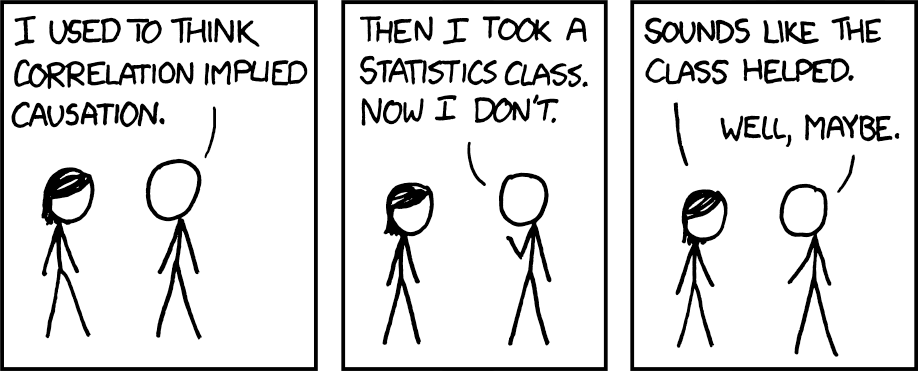

Almost all of our everyday knowledge about cause and effect comes from this kind of intuitive post hoc reasoning. My phone starts acting up after I drop it; someone unfriends me after I post an offensive joke; the fire alarm goes off right after I light a cigarette. As Randall Munroe, creator of xkcd, once put it: “Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing ‘look over there.’” The problem with astrology, homeopathy, and other forms of quack medicine lies in their background causal assumptions, not in the post hoc inferences themselves.

Ad hominem

Perhaps the most famous fallacy of all is the ad hominem. The principle seems simple: when assessing an argument, you should attack the argument, not the person. Play the man instead of the ball, and you’re guilty of ad hominem reasoning. But is it really that simple?

If your ad hominem argument is meant deductively, then yes—it’s invalid. For example: “This researcher is in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry, therefore his study is flawed.” If “therefore” is intended in a strict deductive sense, the argument is clearly invalid: the conclusion doesn’t logically follow. But how often do we actually encounter such rigid ad hominems in real life?

Here’s a more reasonable, plausible version: “This researcher studying the efficacy of a new antidepressant was funded by the company that makes the drug. Therefore, we should take his results with a large grain of salt.” This is far more defensible. It’s what philosophers call a defeasible argument—one that’s provisional, open to revision, and inconclusive. Most real-world arguments work this way. Yes, it has an ad hominem structure, but does that mean we should dismiss it outright?

Courts routinely rely on ad hominem reasoning. Judges can discount witnesses or experts because of bias, conflicts of interest, or hidden agendas. Sure, a biased witness might still tell the truth—but courts aren’t schools of formal logic. Politicians attack the character of their opponents too—and often for very good reason.

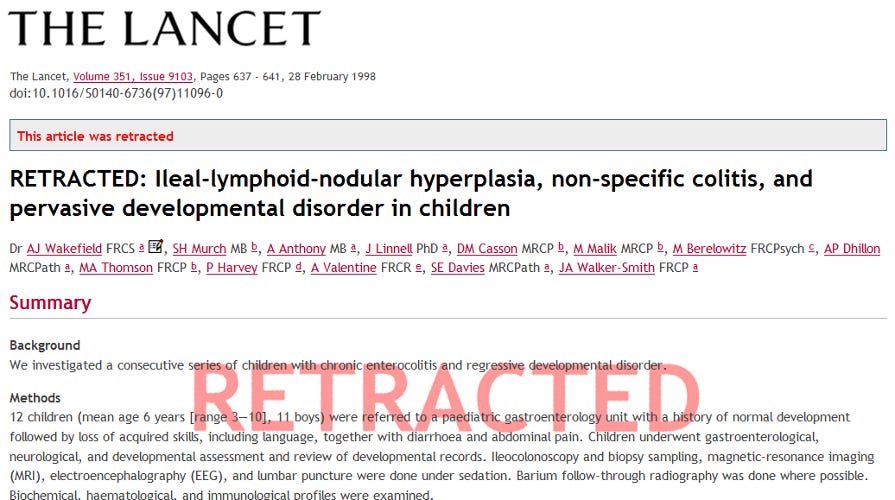

Even in science, despite its lofty rhetoric, personal reputation and status matter enormously. Peer review is anonymous in theory, but once you publish a paper, you’re staking your name and reputation on it. You also have to declare your affiliation, funding sources, and any conflicts of interest. Everyone understands why. A study claiming a link between vaccination and autism by someone who’s funded by anti-vaccination groups isn’t automatically invalid—but you’d be well-advised to take it with a truckload of salt (and in Andrew Wakefield’s case, the study indeed turned out to be fraudulent).

The truth is, we can’t do without ad hominem reasoning, for the simple reason that human knowledge is deeply social. Almost everything we know comes from testimony; only an infinitesimal fraction do we verify ourselves. The rest is, literally, hearsay. No wonder we are so sensitive to the reputation and trustworthiness of our sources.

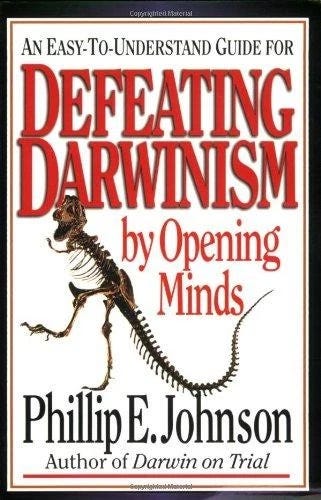

Even Carl Sagan, in The Demon-Haunted World, unwittingly illustrates the limits of the ad hominem fallacy. Trying to be fair and even-handed, he points out that even skeptics sometimes commit ad hominem fallacy, as in this example: “The Reverend Dr. Smith is a known Biblical fundamentalist, so her objections to evolution need not be taken seriously.” As usual, Sagan made up the example himself. It’s a pedagogical straw man—easy to knock down, but far removed from the messy, nuanced reasoning people actually do.

But unless Sagan’s argument is meant deductively (first prong), it’s not fallacious at all (second prong). If we know that Reverend Smith is a Christian fundamentalist who swears by the literal truth of the Bible, any reasonable person would put little stock in his refutation of Darwinian evolution. In fact, you’d probably be better off not wasting your time on it.

Sure, from a purely logical standpoint, even a die-hard creationist could conceivably raise a solid objection against evolution. If you assume that, because of his evangelical faith, the Reverend’s argument must be wrong, you’re committing a deductive error. But who cares?

I’m not denying that some ad hominem arguments are uncalled for or can derail a discussion. But there’s no bright line, and it would be foolish to categorically dismiss all ad hominem considerations. None of this can be captured in a neat, formal argumentation scheme.

Genetic fallacy

In the genetic fallacy, a relative latecomer to the fallacy party, you dismiss something based on its origins. Many religious apologists argue that explaining the evolutionary roots of belief does nothing to undermine God’s existence. But it does. As Nietzsche understood, if you can explain the origins of religious faith in biological terms, then “with the insight into that origin the belief falls away.” Sure, if we possessed incontrovertible evidence for God’s existence, then the genealogy of belief would be irrelevant. But in the absence of such evidence, showing how religious faith can arise without any supernatural input genuinely weakens its credibility.

Consider a few other examples. Some dementia patients reportedly experience a final burst of clarity before death. The author Charles Murray has recently suggested that such “terminal lucidity” points to God or an afterlife. But if neuroscience can explain these episodes in purely neurological terms, supernatural interpretations become unnecessary.

Or take the Ouija board—the supposedly spooky device for communicating with spirits. If the movement of the glass can be explained by the ideomotor effect (tiny, unconscious muscle movements), doesn’t that undercut the ghost story? Yes, strictly speaking, ghosts could still be involved—but that just goes to show the limits of logic. As Joseph Heller’s Yossarian says in Catch-22, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” Deductively, he has a point. But the line is funny precisely because it’s absurd, logic be damned.

Fallacies galore

I could continue to dissect every other “fallacy” on the list, but you’d probably get bored. I’ll quickly run through a few more examples—then you can try it yourself.

The argument from ignorance (argumentum ad ignorantiam) is usually called a fallacy because of the classic dictum: “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” But in real life, it often is evidence, and people seem intuitively aware of this. For example: “Recovered memories about satanic cults sacrificing babies are probably the product of confabulation and suggestion, because we have never found any material traces of these atrocities.” That’s perfectly reasonable. The probabilistic premise is sound: if such cults had existed, we would have found baby corpses—or at least hundreds of missing infants.

The argument from authority (ad verecundiam) claims something is true because an expert said so. But as we’ve seen, almost all our knowledge is testimonial—based on authority. Rejecting arguments from authority entirely would lead to radical skepticism. Once again, context matters. Is the expert truly knowledgeable in this field? What’s their track record on similar claims? Do they have incentives to lie? Do others trust them? In the real world, these questions matter far more than any blanket rule about “ad verecundiam.”

The gambler’s fallacy occurs when you assume that if an event has happened less often than expected, it is somehow “due” next time around. At the roulette table, this belief will reliably lead you astray. But casinos are highly artificial environments designed to produce independent events. Out in the wild, things are different. Events cluster, streak, and correlate, and humans are remarkably good at detecting patterns. In natural settings, what looks like the gambler’s fallacy is often not fallacious at all.

The fallacy of affirming the consequent is a staple of formal logic. From “If A, then B,” you cannot infer “B, therefore A.” The hackneyed textbook example goes like this: “If it rains, the street will be wet. The street is wet. Therefore, it rained.” Well, who knows? Perhaps a firetruck just hosed down your street? The problem is that one person’s “affirming the consequent” is another person’s inference to the best explanation. Anyone stepping outside onto a wet street will almost automatically conclude that it probably rained. That’s not a logical blunder; it’s ordinary causal reasoning. Without this kind of abductive inference, we would have no causal knowledge at all.

A rare breed

Pure fallacies are a rare breed. You mostly spot them in logic textbooks or books about irrationality—not in real life. If you think you’ve caught one, chances are you missed something and the case isn’t so clear-cut. Maybe you exaggerated the force of an argument, turning an defeasible argument into a deductive one, glossing over probabilistic assumptions, or stripping away context and knocking it down in the abstract. In other words, you may have built a straw man—another supposed “fallacy” that can’t be formally defined.

In his sarcastic little book The Art of Being Right (1896), Arthur Schopenhauer summed up every philosopher and educator’s dream: “It would be a very good thing if every trick could receive some short and obviously appropriate name, so that when a man used this or that particular trick, he could be at once reproached for it.” That would be splendid indeed. But real life is messier.

Humans love to pigeonhole things into neat little boxes, and the traditional taxonomy of fallacies—especially the ones with pretentious Latin names—is irresistible in that regard. Encounter an argument you don’t like? Just squeeze it into a pre-established category and blow the whistle: fallacy! Making causal inferences from a sequence of events? Post hoc ergo propter hoc! Relying on an expert for a point? Ad verecundiam! Challenging someone’s credibility? Ad hominem!

None of this is to say that ad hominem reasoning or appeals to authority are completely beyond reproach. These aren’t logical errors per se, but overreliance on them can signal weakness. Personally, when I publish a polemical piece and fret over possible flaws that I may have overlooked, I’m oddly relieved when critics attack my character or question my credentials. Not because those points are logically fallacious, but because it usually means my argument didn’t contain any obvious falsehoods after all. If there were glaring flaws, that’s where the fire would be directed. The resort to ad hominem is therefore strangely reassuring.

Nor am I claiming that clear-cut errors of logic and probability never happen in real life. The prosecutor’s fallacy, for instance, really deserves its name. It’s a recurring and serious mistake in the judicial system, reversing the probability of evidence given innocence with the probability of innocence given evidence.

But most of the other famous fallacies? They mostly exist in textbooks. In the classroom, you can hand students neat taxonomies, toy examples, and bright red warning signs: “Don’t fall for this!” It feels satisfying and gives a sense of mastery: you tick off ad hominem, post hoc, straw man, and move on.

Out in the wild, however, things aren’t black-and-white. An ad hominem might be perfectly sensible, a post hoc argument often reasonable, and even a slippery slope occasionally warranted.

In my experience, fallacy theory is not just useless—it can be actively harmful. It encourages intellectual laziness, offering high-minded excuses to dismiss any argument you don’t like. It impoverishes debate by pretending that messy, real-world disagreements can be resolved with the blunt tools of formal logic. You end up like my students: slightly paranoid, dismissive, and ironically less critical than when you started.

Most of all, fallacy theory misleads us about the real sources of human irrationality. Most people intuitively grasp the basic rules of logic and probability—we wouldn’t have survived otherwise. Human reason is a bag of tricks and heuristics, mostly accurate in the environments in which we evolved, but easily led astray in modern life. And it is strategic and self-serving, motivated to reach conclusions that serve our own interests.

Despite its flaws and foibles, though, human reasoning is far more sophisticated and subtle than the theory of “fallacies” suggests.

le keep falling for these reasoning traps, they end up believing all sorts of crazy stuff. Still, the theory offers hope: if you memorize the classics—ad hominem, post hoc, straw man—you will inoculate yourself against them.

It’s a neat little story, and I used to believe it too. Not anymore. I’ve become a fallacy apostate.

Growing doubts

My doubts began when I was still in academia, teaching critical thinking to philosophy students and science majors alike. Fallacies are a favorite chapter in such courses. In some ways, they are ideal teaching material: they come in tidy lists and seem easy to apply. Many trace back to Aristotle and still parade under their Latin names—ad hominem, ad populum, ad ignorantiam, ad verecundiam (better known as the argument from authority), the slippery slope, affirming the consequent, and so on.

So I dutifully taught my students the standard laundry list and then challenged them to put theory into practice. Read a newspaper article, or watch a political debate—and spot the fallacies!

After a few years, I abandoned the assignment. The problem? My students turned paranoid. They began to see fallacies everywhere. Instead of engaging with the substance of an argument, they hurled labels and considered the job done. Worse, most of the “fallacies” they identified did not survive closer scrutiny.

It would be too easy to blame my students. When I tried the exercise myself, I had to admit that I mostly came away empty-handed. Clear-cut fallacies are surprisingly hard to find in real life. So what do you do if your professor tells you to hunt for fallacies and you can’t find any? You lower the bar. To satisfy the assignment, you expand your definition.

I turned to the classics to see whether I was missing something. The Demon-Haunted World by Carl Sagan is one of the most celebrated books on critical thinking and everyday irrationality. Like many works in the genre, it contains a dedicated section on fallacies, where Sagan dutifully lists the usual suspects. The curious thing, however, is that he rarely puts them to work in the rest of the book. The section feels almost perfunctory—as if, close to the deadline, Sagan’s editor had told him: “Shouldn’t you include a list of fallacies somewhere, Carl?” As in many textbooks, real-life examples are scarce. Instead, we get tidy, invented toy arguments that are easy to knock down.

Sagan is not alone in paying lip service to fallacy theory while making little real use of it. Here’s the most popular educational video on fallacies, with millions of views, which consists entirely of toy examples.

Or consider this recent viral TikTok video of a guy fighting with his girlfriend, racking up twelve logical fallacies in under two minutes. It’s an impressive performance—but obviously scripted. Another collection of toy examples, and not very persuasive ones at that.

All of this makes you wonder: if fallacies are as ubiquitous as we’re told, why is the theory always illustrated with invented toy examples?

The Fallacy Fork

Some time ago, I published a paper in the journal Argumentation with two colleagues (including my friend Massimo Pigliucci) arguing that fallacy theory should be abandoned. The paper is still regularly cited, and looking back I think it has aged pretty well (which can’t be said of all my old papers). I won’t bore you with the technical details, but since “fallacies” are constantly invoked in political debates, online and off, I thought it would be interesting to explain the core argument. Even if formal logic leaves you cold, you’ve probably seen how fallacy labels get tossed around in discussions. Maybe you’ve felt the frustration without quite being able to put your finger on it. Our paper tries to explain that irk.

Philosophers have attempted to define fallacies using formal argumentation schemes. The approach is appealing: it promises a systematic way to identify bad arguments across contexts. In practice, however, it proves remarkably difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Here is the crux: every so-called fallacy closely resembles forms of reasoning that are perfectly legitimate, depending on the context. In formal terms, good and bad arguments are often indistinguishable. Worse, there is almost always a continuum between strong and weak arguments. You cannot capture that gradient in a rigid formal scheme. As my friends Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber succinctly put it in The Enigma of Reason: “most if not all fallacies on the list are fallacious except when they are not.”

We show this by using what we call the Fallacy Fork. This destructive dilemma forces you to choose between two unpalatable options. First, I’ll lay out the two prongs of the dilemma. Then I’ll turn to some examples.

(A) You define your fallacy using a neat deductive argument scheme. In a valid deductive argument, the conclusion must follow inexorably from the premises. If the premises are true yet the conclusion could still be false, the argument is invalid—case closed. The trouble is that, in real life, you almost never encounter such clean, airtight blunders. You can invent textbook examples, sure, but flesh-and-blood cases are surprisingly rare.

(B) So you loosen things up and abandon the strict realm of deductive logic. You add some context and nuance. Now you can capture plenty of real-life arguments. Great. Except there’s a catch: once you relax the standard, your “fallacy” stops being fallacious. It turns into a perfectly ordinary move in everyday reasoning—sometimes weak, sometimes strong, but not obviously irrational.

Let’s see how some of the most famous fallacies fare when confronted with the Fallacy Fork.

Post hoc fallacy

As the saying goes: correlation does not imply causation. If you think otherwise, logic textbooks will tell you that you’re guilty of the fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc. You can formalize it like this:

If B follows A, then A is the cause of B.

Clearly, this is false. Any event B is preceded by countless other events. If I suddenly get a headache, which of the myriad preceding events should I blame? That I had cornflakes for breakfast? That I wore blue socks? That my neighbor wore blue socks?

It’s easy to mock this fallacy—websites like Spurious Correlations offer graphs showing correlations between margarine consumption and divorce rates, or between the number of people who drowned by falling into a pool and the number of Nicholas Cage films released per year.

The problem is that not even the most superstitious person really believes that just because A happened before B, A must have caused B. Sure, in strict deductive terms, post hoc ergo propter hoc is a fallacy—but real-life examples are almost nonexistent. That’s the first prong of the Fallacy Fork.

So what do real-life post hoc arguments actually look like? More like this: “If B follows shortly after A, and there’s some plausible causal mechanism linking A and B, then A is probably the cause of B.” Many such arguments are entirely plausible—or at least not obviously wrong. Context is everything.

Imagine you eat some mushrooms you picked in the forest. Half an hour later, you feel nauseated, so you put two and two together: “Ugh. That must have been the mushrooms.” Are you committing a fallacy? Yes, says your logic textbook. No, says common sense—at least if your inference is meant to be probabilistic.

Here, the inference is actually reasonable, assuming a few tacit things:

Some mushrooms are toxic.

It’s easy for a layperson to mistake a poisonous mushroom for a harmless one.

Nausea is a common symptom of food poisoning.

You don’t normally feel nauseated.

If you want, you can even spell this out in probabilistic terms. Consider the last premise—the base rate. If you usually have a healthy stomach, the mushroom is the most likely culprit. If, on the other hand, you frequently suffer from gastrointestinal problems, the post hoc inference becomes much weaker.

Almost all of our everyday knowledge about cause and effect comes from this kind of intuitive post hoc reasoning. My phone starts acting up after I drop it; someone unfriends me after I post an offensive joke; the fire alarm goes off right after I light a cigarette. As Randall Munroe, creator of xkcd, once put it: “Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing ‘look over there.’” The problem with astrology, homeopathy, and other forms of quack medicine lies in their background causal assumptions, not in the post hoc inferences themselves.

Ad hominem

Perhaps the most famous fallacy of all is the ad hominem. The principle seems simple: when assessing an argument, you should attack the argument, not the person. Play the man instead of the ball, and you’re guilty of ad hominem reasoning. But is it really that simple?

If your ad hominem argument is meant deductively, then yes—it’s invalid. For example: “This researcher is in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry, therefore his study is flawed.” If “therefore” is intended in a strict deductive sense, the argument is clearly invalid: the conclusion doesn’t logically follow. But how often do we actually encounter such rigid ad hominems in real life?

Here’s a more reasonable, plausible version: “This researcher studying the efficacy of a new antidepressant was funded by the company that makes the drug. Therefore, we should take his results with a large grain of salt.” This is far more defensible. It’s what philosophers call a defeasible argument—one that’s provisional, open to revision, and inconclusive. Most real-world arguments work this way. Yes, it has an ad hominem structure, but does that mean we should dismiss it outright?

Courts routinely rely on ad hominem reasoning. Judges can discount witnesses or experts because of bias, conflicts of interest, or hidden agendas. Sure, a biased witness might still tell the truth—but courts aren’t schools of formal logic. Politicians attack the character of their opponents too—and often for very good reason.

Even in science, despite its lofty rhetoric, personal reputation and status matter enormously. Peer review is anonymous in theory, but once you publish a paper, you’re staking your name and reputation on it. You also have to declare your affiliation, funding sources, and any conflicts of interest. Everyone understands why. A study claiming a link between vaccination and autism by someone who’s funded by anti-vaccination groups isn’t automatically invalid—but you’d be well-advised to take it with a truckload of salt (and in Andrew Wakefield’s case, the study indeed turned out to be fraudulent).

The truth is, we can’t do without ad hominem reasoning, for the simple reason that human knowledge is deeply social. Almost everything we know comes from testimony; only an infinitesimal fraction do we verify ourselves. The rest is, literally, hearsay. No wonder we are so sensitive to the reputation and trustworthiness of our sources.

Even Carl Sagan, in The Demon-Haunted World, unwittingly illustrates the limits of the ad hominem fallacy. Trying to be fair and even-handed, he points out that even skeptics sometimes commit ad hominem fallacy, as in this example: “The Reverend Dr. Smith is a known Biblical fundamentalist, so her objections to evolution need not be taken seriously.” As usual, Sagan made up the example himself. It’s a pedagogical straw man—easy to knock down, but far removed from the messy, nuanced reasoning people actually do.

But unless Sagan’s argument is meant deductively (first prong), it’s not fallacious at all (second prong). If we know that Reverend Smith is a Christian fundamentalist who swears by the literal truth of the Bible, any reasonable person would put little stock in his refutation of Darwinian evolution. In fact, you’d probably be better off not wasting your time on it.

Sure, from a purely logical standpoint, even a die-hard creationist could conceivably raise a solid objection against evolution. If you assume that, because of his evangelical faith, the Reverend’s argument must be wrong, you’re committing a deductive error. But who cares?

I’m not denying that some ad hominem arguments are uncalled for or can derail a discussion. But there’s no bright line, and it would be foolish to categorically dismiss all ad hominem considerations. None of this can be captured in a neat, formal argumentation scheme.

Genetic fallacy

In the genetic fallacy, a relative latecomer to the fallacy party, you dismiss something based on its origins. Many religious apologists argue that explaining the evolutionary roots of belief does nothing to undermine God’s existence. But it does. As Nietzsche understood, if you can explain the origins of religious faith in biological terms, then “with the insight into that origin the belief falls away.” Sure, if we possessed incontrovertible evidence for God’s existence, then the genealogy of belief would be irrelevant. But in the absence of such evidence, showing how religious faith can arise without any supernatural input genuinely weakens its credibility.

Consider a few other examples. Some dementia patients reportedly experience a final burst of clarity before death. The author Charles Murray has recently suggested that such “terminal lucidity” points to God or an afterlife. But if neuroscience can explain these episodes in purely neurological terms, supernatural interpretations become unnecessary.

Or take the Ouija board—the supposedly spooky device for communicating with spirits. If the movement of the glass can be explained by the ideomotor effect (tiny, unconscious muscle movements), doesn’t that undercut the ghost story? Yes, strictly speaking, ghosts could still be involved—but that just goes to show the limits of logic. As Joseph Heller’s Yossarian says in Catch-22, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” Deductively, he has a point. But the line is funny precisely because it’s absurd, logic be damned.

Fallacies galore

I could continue to dissect every other “fallacy” on the list, but you’d probably get bored. I’ll quickly run through a few more examples—then you can try it yourself.

The argument from ignorance (argumentum ad ignorantiam) is usually called a fallacy because of the classic dictum: “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” But in real life, it often is evidence, and people seem intuitively aware of this. For example: “Recovered memories about satanic cults sacrificing babies are probably the product of confabulation and suggestion, because we have never found any material traces of these atrocities.” That’s perfectly reasonable. The probabilistic premise is sound: if such cults had existed, we would have found baby corpses—or at least hundreds of missing infants.

The argument from authority (ad verecundiam) claims something is true because an expert said so. But as we’ve seen, almost all our knowledge is testimonial—based on authority. Rejecting arguments from authority entirely would lead to radical skepticism. Once again, context matters. Is the expert truly knowledgeable in this field? What’s their track record on similar claims? Do they have incentives to lie? Do others trust them? In the real world, these questions matter far more than any blanket rule about “ad verecundiam.”

The gambler’s fallacy occurs when you assume that if an event has happened less often than expected, it is somehow “due” next time around. At the roulette table, this belief will reliably lead you astray. But casinos are highly artificial environments designed to produce independent events. Out in the wild, things are different. Events cluster, streak, and correlate, and humans are remarkably good at detecting patterns. In natural settings, what looks like the gambler’s fallacy is often not fallacious at all.

The fallacy of affirming the consequent is a staple of formal logic. From “If A, then B,” you cannot infer “B, therefore A.” The hackneyed textbook example goes like this: “If it rains, the street will be wet. The street is wet. Therefore, it rained.” Well, who knows? Perhaps a firetruck just hosed down your street? The problem is that one person’s “affirming the consequent” is another person’s inference to the best explanation. Anyone stepping outside onto a wet street will almost automatically conclude that it probably rained. That’s not a logical blunder; it’s ordinary causal reasoning. Without this kind of abductive inference, we would have no causal knowledge at all.

A rare breed

Pure fallacies are a rare breed. You mostly spot them in logic textbooks or books about irrationality—not in real life. If you think you’ve caught one, chances are you missed something and the case isn’t so clear-cut. Maybe you exaggerated the force of an argument, turning an defeasible argument into a deductive one, glossing over probabilistic assumptions, or stripping away context and knocking it down in the abstract. In other words, you may have built a straw man—another supposed “fallacy” that can’t be formally defined.

In his sarcastic little book The Art of Being Right (1896), Arthur Schopenhauer summed up every philosopher and educator’s dream: “It would be a very good thing if every trick could receive some short and obviously appropriate name, so that when a man used this or that particular trick, he could be at once reproached for it.” That would be splendid indeed. But real life is messier.

Humans love to pigeonhole things into neat little boxes, and the traditional taxonomy of fallacies—especially the ones with pretentious Latin names—is irresistible in that regard. Encounter an argument you don’t like? Just squeeze it into a pre-established category and blow the whistle: fallacy! Making causal inferences from a sequence of events? Post hoc ergo propter hoc! Relying on an expert for a point? Ad verecundiam! Challenging someone’s credibility? Ad hominem!

None of this is to say that ad hominem reasoning or appeals to authority are completely beyond reproach. These aren’t logical errors per se, but overreliance on them can signal weakness. Personally, when I publish a polemical piece and fret over possible flaws that I may have overlooked, I’m oddly relieved when critics attack my character or question my credentials. Not because those points are logically fallacious, but because it usually means my argument didn’t contain any obvious falsehoods after all. If there were glaring flaws, that’s where the fire would be directed. The resort to ad hominem is therefore strangely reassuring.

Nor am I claiming that clear-cut errors of logic and probability never happen in real life. The prosecutor’s fallacy, for instance, really deserves its name. It’s a recurring and serious mistake in the judicial system, reversing the probability of evidence given innocence with the probability of innocence given evidence.

But most of the other famous fallacies? They mostly exist in textbooks. In the classroom, you can hand students neat taxonomies, toy examples, and bright red warning signs: “Don’t fall for this!” It feels satisfying and gives a sense of mastery: you tick off ad hominem, post hoc, straw man, and move on.

Out in the wild, however, things aren’t black-and-white. An ad hominem might be perfectly sensible, a post hoc argument often reasonable, and even a slippery slope occasionally warranted.

In my experience, fallacy theory is not just useless—it can be actively harmful. It encourages intellectual laziness, offering high-minded excuses to dismiss any argument you don’t like. It impoverishes debate by pretending that messy, real-world disagreements can be resolved with the blunt tools of formal logic. You end up like my students: slightly paranoid, dismissive, and ironically less critical than when you started.

Most of all, fallacy theory misleads us about the real sources of human irrationality. Most people intuitively grasp the basic rules of logic and probability—we wouldn’t have survived otherwise. Human reason is a bag of tricks and heuristics, mostly accurate in the environments in which we evolved, but easily led astray in modern life. And it is strategic and self-serving, motivated to reach conclusions that serve our own interests.

Despite its flaws and foibles, though, human reasoning is far more sophisticated and subtle than the theory of “fallacies” suggests.

Dear Maarten,

Allow me to begin by expressing my gratitude for the clarity and provocation of your reflections. Few things are more valuable in philosophy than a thesis that unsettles our intellectual habits, for it is through such disturbances that thought is compelled to refine itself.

I have long suspected that our treatment of logical fallacies has acquired a moral tone it does not deserve. To accuse a man of committing a fallacy is often less an act of illumination than one of quiet condemnation. Yet error, properly understood, is not a vice. We must be cautious not to confuse being mistaken with being morally deficient, nor truth with goodness. The history of thought shows us repeatedly that progress is made by those willing to err in earnest rather than by those who merely police the errors of others.

There is, moreover, something valuable and meaningful hidden within imperfect reasoning. Human thought is not a geometric proof; it is exploratory, tentative, and frequently inconsistent. If we were to reject every argument that bears the mark of logical imperfection, we would discard much of what has guided inquiry forward. Pointing out each logical misstep does not, by itself, teach us how to reason well. It may instead cultivate a sterile cleverness — the ability to win arguments without advancing understanding.

One might also recall that there exist demonstrations suggesting that no logical system can achieve complete self-sufficiency. If completeness itself eludes our most rigorous formal structures, it would seem rather arrogant to demand flawless coherence from ordinary human reasoning. To morally judge others on the basis of such imagined completeness neither improves our character nor strengthens the process of reasoning; it merely introduces anxiety where intellectual courage ought to reside.

There is another danger. The naming of fallacies can become a rhetorical weapon — a means of closing conversation rather than opening it. When the aim shifts from pursuing truth to securing victory, dialogue withers. To refute another’s supposed thinking errors is no guarantee that our own reasoning is thereby purified. Intellectual humility requires us to remember that the exposure of error is only valuable insofar as it invites further inquiry.

Let us therefore resist the temptation to turn logic into a tribunal. Better, I think, to regard reasoning as a cooperative venture in which fallibility is not only inevitable but indispensable. We learn not by pretending to be infallible, but by remaining open — both to correction and to the partial wisdom contained in views not yet fully formed.

Thank you for your insights, Maarten. They remind us that philosophy is at its best when it encourages courage in thinking rather than fear of being wrong.

With sincere regard,

Human history is dominated by mass delusions of 2 kinds. POLITICAL delusions are based upon exaggerated fears that can be blamed on that tribe over there. RELIGIOUS delusions are based upon exaggerated fears that can be blamed on our own imagined collective guilt.

Both are driven by true believing zealots striving for moral status and the power to enforce. All tyrants believe that they are on the side of the angels.

These delusions are not the result of the standard logical fallacies (except self-contradiction). Instead they arise from false premises that are often assumed and unstated.

My guess is that the most damaging false premise is the intuitions that life is zero sum, and that resources deplete. Instead humans earn wealth by creating it, and they invent new resources from formerly useless stuff.