Gut Feelings (Part I)

How Evolved Intuitions Shape and Distort Our Beliefs About Food

[Last week I spoke on the future of food at Reboot Food in Helsinki, a festival run by WePlanet—an energetic young NGO I hesitate to call “environmentalist” or “green”, since these labels have been corrupted beyond redemption. Unlike many groups flying the green banner, the people at WePlanet are true progressives. They embrace technological innovation and ingenuity, they believe in growth and abundance, and they refuse to regard humans (or just WEIRD humans) as a blight on the planet. They’re adjacent to ecomodernism and the abundance movement, though most of the people I talked to prefer the term eco-humanist. WePlanet invited me after I appeared on their Bad Ideas podcast to talk about the miracle of fossil fuels. As I warned the WePlaneteers, I’m no food expert—but I have spent a lot of time studying the cultural evolution of misbeliefs. Why are certain illusions so irresistible to the human mind? Why is science often so hard to digest while pseudoscience goes down like comfort food? I set out to turn my talk into a written piece, keeping the visual vibe of my slide deck. That modest plan promptly ballooned into 6,000 words, so I’m serving it in two separate courses.]

Woody Allen once joked that the brain was his “second favorite organ.” Yet like every other organ in the body, it was sculpted by natural selection to handle the recurring challenges of our ancestors. The heart pumps blood, the lungs supply oxygen, and the stomach and intestines break down food to draw out nutrients.

And Woody’s runner-up favorite? It’s reductive to pin the brain to any simple job, but one of its most important roles is building an approximately accurate model of the outside world. Emphasis on “approximate”. Our brains didn’t evolve to unravel the structure of the cosmos, but to deliver a quick-and-dirty roadmap to navigate the kinds of environments our ancestors were likely to encounter—telling edible from toxic foods, tracking animals, and steering clear of predators, parasites, precipices, and other routine hazards. As the philosopher W.V.O. Quine once delicately put it: “Creatures inveterately wrong in their inductions have a pathetic but praiseworthy tendency to die before reproducing their kind".

But while false beliefs about these recurrent dangers may be highly detrimental to your fitness, evolution does not care about truth in and of itself. At the end of the day, the only currency of natural selection is survival and reproduction. If some creature can achieve reproductive success more efficiently through a false belief, then those misguided individuals will thrive and multiply.

Psychologists and philosophers have floated various such “adaptive misbeliefs” that evolution might directly have favored, but the list is not very extensive: belief in free will, inflated self-confidence and optimism, mind/body dualism, moral realism. In any event, evolution rarely selects for specific beliefs, whether true or false. Instead, it equips us with certain mental habits that mostly deliver true beliefs, but may produce some inaccurate ones as an unintended, yet tolerable, side effect. Or with thought patterns that produce mostly accurate beliefs in our ancestral environment, but lead us astray in a modern one that evolution never anticipated.

A rich source of such deeply-ingrained intuitions and habits of mind is food—which should of course not surprise us, given how central it’s always been to survival. Let’s zoom in on one of these that still shapes how we think about what we eat: essentialism.

Invisible essences

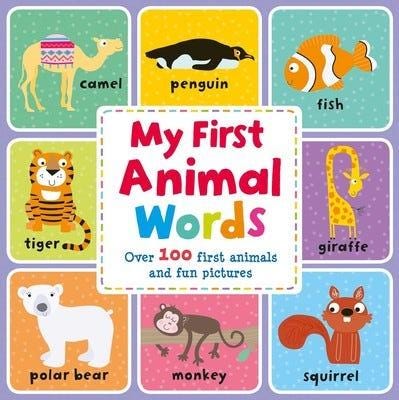

If you're looking to entertain an infant or toddler, a picture book filled with animals is a surefire hit. Kids absolutely love flipping through pages of adorable creatures and proudly naming each one—putting every animal into its rightful category. Even when illustrations are abstract or whimsical, they rarely get confused—a giraffe is still a giraffe. As long as it has a long neck, four legs, and big spots, they’ll call it right every time.

Young children take great delight in sorting animals into the “right” boxes, guided by firm intuitions about what belongs and what doesn’t. Psychologists call this essentialism: the tendency to divide the world into fixed, non-overlapping categories—often arranged in a neat hierarchy—and to believe that membership comes from some invisible essence.

Experiments reveal that children grasp, even at a young age and without any formal teaching, that an animal's true essence does not lie in its superficial appearance, but is tied to some invisible quality inherent to it. In one classic experiment by the psychologist Susan Gelman, kids were shown a picture of adorable piglets swaddled in tiger fur and nursing from a tiger mom.

What will happen to piglets that are raised by a tigress? Will they start growling and hunting down prey? Most kids understand, without explicit instruction, that the piglets will still grunt, oink and wallow in the mud. Each piglet has an invisible porcine essence that can’t be swapped out by a costume change or an unfamiliar setting. By the same token, children know that a walking stick, leaf-like though it may appear, is still an insect and it will act like one, foraging for food and dodging predators.

This essentialist mindset, which is deeply ingrained and exists across human cultures, was quite helpful to navigate in the environment of our hominid ancestors. By sorting a variety of objects into fixed categories, you can quickly predict what to expect in any given situation. It’s not just this particular striped and whiskered animal that might pounce on you—it’s any creature that falls into the same category.

Psychological essentialism sheds light on various illusions and misconceptions about the living world, beginning with the theory of evolution itself. Evolution by natural selection can feel counterintuitive because it requires us to accept that gradual, imperceptible changes can eventually lead to differences that bridge the boundaries between different species. In the Darwinian worldview, there are no rigid species categories, only populations of organisms (or genes) that are in a constant state of flux. When two populations diverge enough to become reproductively isolated, we label them as different “species”. Still, there’s no essential definition for any species, and even reproductive isolation comes in degrees.

For someone with an intuitive essentialist mindset, common ancestry is a tough pill to swallow. It’s not just that we share a distant ancestor with chimps and bonobos—we’re also related to giraffes, tapeworms, cucumbers, and cockroaches. One of my favorite illustrations of this mental hiccup is the infamous “crocoduck” you see below, a fictional creature creationists like to trot out to mock the idea of intermediate species.

How could any creature be halfway between a crocodile and a duck? Preposterous! If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck. If not, well, then it might be a crocodile—or something else entirely.

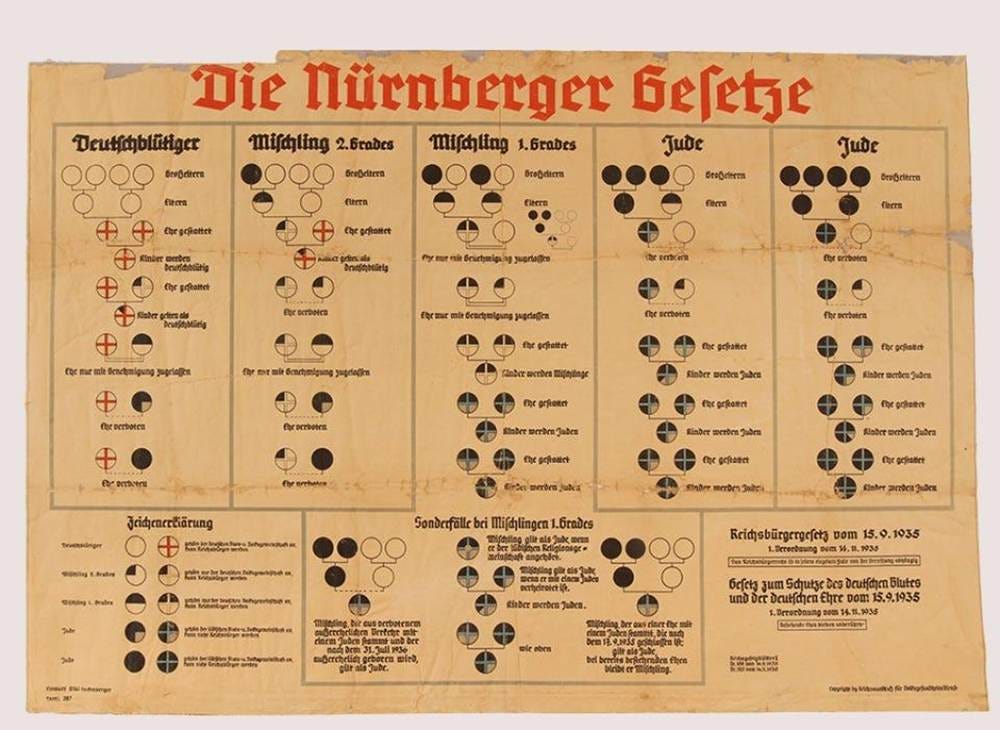

The crocoduck is a particularly glaring example of essentialism in action, but there are plenty of subtler versions out there. Even people who accept the theory of evolution are often tempted to ask whether a given hominid fossil was “already human” or “still simian”. But this question is wrongheaded because it implies that there’s a rigid and timeless divide between “human” and “ape,” and each fossil can be categorised as either the one or the other. In reality, human evolution shows a continuum: species blend, overlap, and branch in intricate and messy ways, making species boundaries little more than arbitrary labels we attach to a gradual evolutionary process. And let’s not forget the antiquated belief in distinct human “races”—fixed, non-overlapping categories with inherent traits. That’s another prime example of intuitive essentialism running wild.

So far we’ve been talking about factual misbeliefs about nature, but intuitive essentialism also gets under our skin morally and emotionally. As the history of racism makes painfully clear—see for instance the various anti-miscegenation laws—the notion of “mixing” races was cast as polluting, disgusting, and shameful. It’s not just that nature is imagined as neatly divided into separate kinds; it’s that people think this is how it should be. Any attempt to transgress these natural boundaries is perceived as deeply wrong.

Frankenfood

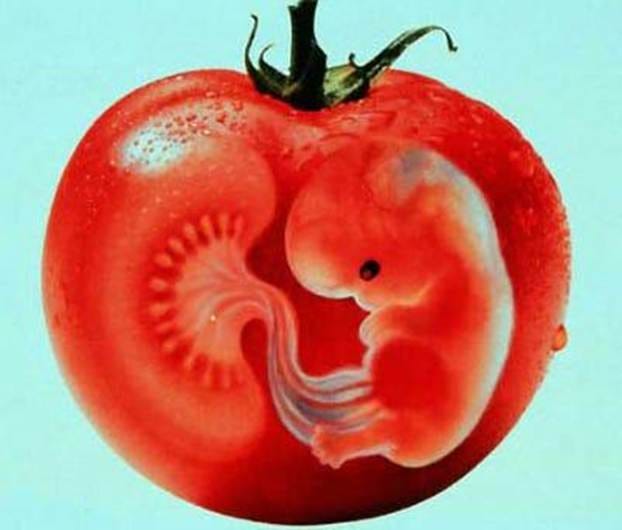

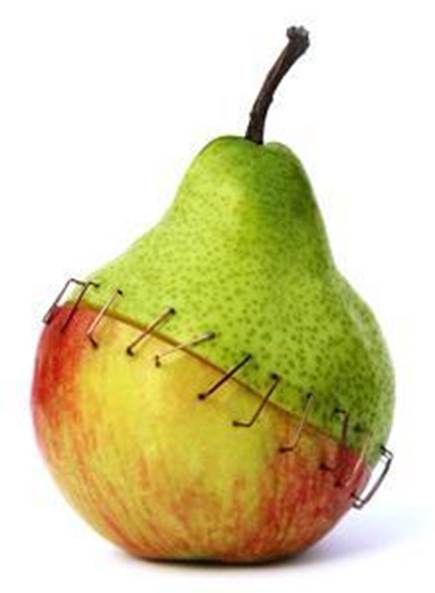

And now we get to our intuitive “gut feelings” about food. A prime reason why GMO foods (Genetically Modified Organism) remain so controversial, and are still banned in many countries, is the pervasive sense that this technology violated Nature’s boundaries. Genes and DNA have come to be regarded as an organism’s inviolable essence, so tinkering with them feels inherently suspect. Not coincidentally, that unease peaks with transgenesis—the insertion of genes from one species into another to create a desired trait, such as adding an antifreeze gene from a fish to a tomato.

Why are so many people terrified of GMOs, and why do so many food companies trumpet “GMO-free” labels, even in places where GMOs are already banned? If you’re looking for a proximate cause, then of course you have to look at the steady drumbeat of fear-mongering propaganda from environmental NGOs and activists. But the deeper question is why those campaigns hit the psychological jackpot in the first place. In many ways, the success of these campaigns took even the campaigners by surprise. Almost by accident, organizations like Greenpeace discovered that buzzwords like “Frankenfood”, and lurid images such as the ones below, were extraordinarily potent—both as propaganda and as fund-raising hooks (“Give us your money so we can protect your children from those horrible genetic freaks!”).

A few years ago my friend and colleague Stefaan Blancke co-authored a paper in Trends in Plant Science along with GMO pioneer Marc Van Montagu and some other colleagues from the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology. Their focus? The intuitive allure behind public opposition to GMO foods. As they point out, anti-GMO groups have cleverly “tapped into people's intuitions to promote their cause,” making their campaign all the more compelling to our essentialist minds.

It is also striking that GMO food encounters far more opposition than other applications of GMO technology. Medical insulin used to be extracted from the pancreas of pigs or cows (which required inordinate numbers of animals), but nowadays almost all insulin is synthesized by genetically modified yeast. Millions of diabetes patients don’t seem to be bothered by this. Likewise, almost all our bank notes contain Bt-cotton, a GMO variant that protects the plants against a nasty pest called bollworm. This means that your average hipster ends up paying for his organic and GMO-free veggies with GMO bank notes. Most people are simply not aware of this, but even if you would point out the irony, I suspect some activists would just shrug it off. As long as it doesn’t end up in their mouths, it won’t raise any alarms.

So why then do we get such a strong and visceral reaction when GMOs end up on our plates? The clue is in the emotion itself. For a lot of people, GMO food is simply disgusting. Disgust is one of our most powerful emotions, which evolved to help us avoid pathogens and poisons. When it comes to GMO foods, the intuition that kicks in is that inserting tampering with DNA makes a plant or animal impure—and therefore unsafe to eat. Insulin injections, by contrast, don’t trip those ancient wires because they are a modern medical practice our brains haven’t built any automatic reaction to. If anything, the idea of shooting up some pig-derived pancreas extracts probably sparks more of a “yuck” response than the thought of using clean, lab-synthesized insulin.

Harmony with nature

Religious believers sometimes object to GMO technology on the grounds that it is akin to “playing God”—as if we’re claiming the divine right to create new forms of life. But this argument is not exclusively tied to specific religious doctrines and commandments; it's a sentiment shared even by those who don’t adhere to any faith. Many modern environmentalists, despite being atheists, still maintain a quasi-religious belief in a natural order that we tamper with at our own risk. Some personify this order as Mother Nature or Gaia, but the underlying theory remains the same: nature is a harmonious whole, a complex and delicate web where every element has its role. Disturbing this balance isn't just reckless; it feels fundamentally wrong.

It might be too generous to call this belief in natural harmony a “theory”, a fully fleshed-out set beliefs. It’s more of an inchoate sentiment—vague and poorly defined—that can take shape in different ways. In some versions, nature (or even the Earth itself) was in a state of delicate equilibrium until Homo sapiens arrived on the scene. In others, humans lived in harmony with nature until the advent of agriculture changed everything, or until Christianity burst onto the scene. Or at the very latest, until the industrial revolution. The details vary, but the story always follows a similar arc: once upon a time we lived in paradise, but then we reached for some forbidden fruit and everything fell apart. And the underlying moral equation is always as follows:

● Natural = good, pure, innocent, authentic, wholesome, harmonious

● Unnatural = evil, corrupt, spoiled, fake, dangerous, discordant

The most famous expression of this moral division is the opening sentence of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s book Emile: “Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man.” Still, it would be too simple to pin the blame for one of philosophy’s most consequential fallacies on Rousseau alone. (Come to think of it, doing so would replay the very moral fable we’re trying to retire: “Once upon a time, everything was great, but then a French philosopher came along and everything went down the drain!”).

Instead, we should consider why Rousseau’s stark contrast resonates with so many people. Why are millions of consumers drawn to anything labeled “organic,” “all-natural,” “wholesome,” “eco-friendly,” or “holistic,” even if they aren’t quite sure what these terms really mean?

A modern luxury

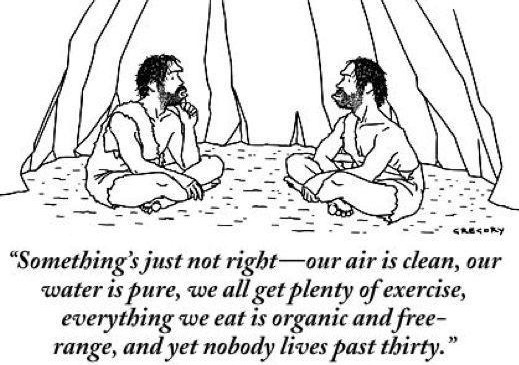

If you’re living as a hunter-gatherer, some versions of the view that "natural = good" and "unnatural = bad" might actually make sense. The very idea of “adaptation” suggests that an organism has evolved to thrive within a specific ecological niche, and straying too far beyond that can be risky. You want to consume the foods your body is designed to metabolize and stick close to the environment where your ancestors thrived. We shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss people who wish to respect the time-honored traditions of their forebears, while saying: “We’ve always done it this way; this is our tradition, it’s just the natural order.”

In pre-modern societies, however, the tendency to idealize all things “natural” is often tempered by, well, reality. Pre-modern and indigenous peoples understood that nature is both awe-inspiring and perilous, filled with dangers ranging from bloodthirsty predators to flesh-eating parasites, from the capriciousness of extreme weather to the threats of infectious disease. Nature isn’t a nurturing mother or a benevolent goddess—not even metaphorically. To survive, you had to either tame her or keep her at arm’s length. Nature commanded respect precisely because she could take your life in an instant or or starve you by degrees. In nearly every corner of the globe, there are several months per year when, without clothing and campfires and shelter, a few hours of exposure to the elements amounted to a death sentence.

In affluent societies, by contrast, the urge to romanticize nature is allowed to run unchecked. Industrialized westerners like to think that indigenous people are the ones who truly know how to live in harmony with nature, but that’s mostly projection on our part. It isn’t the so-called “primitives” who romanticize nature; it’s modern folks, precisely because we no longer face its hardships. The more we’re buffered from the dangers of the natural world, the more estranged we become. With all the comforts of contemporary life at our fingertips, it’s all too easy to indulge in the fantasy of an original harmony with nature that we lost somewhere along the way.

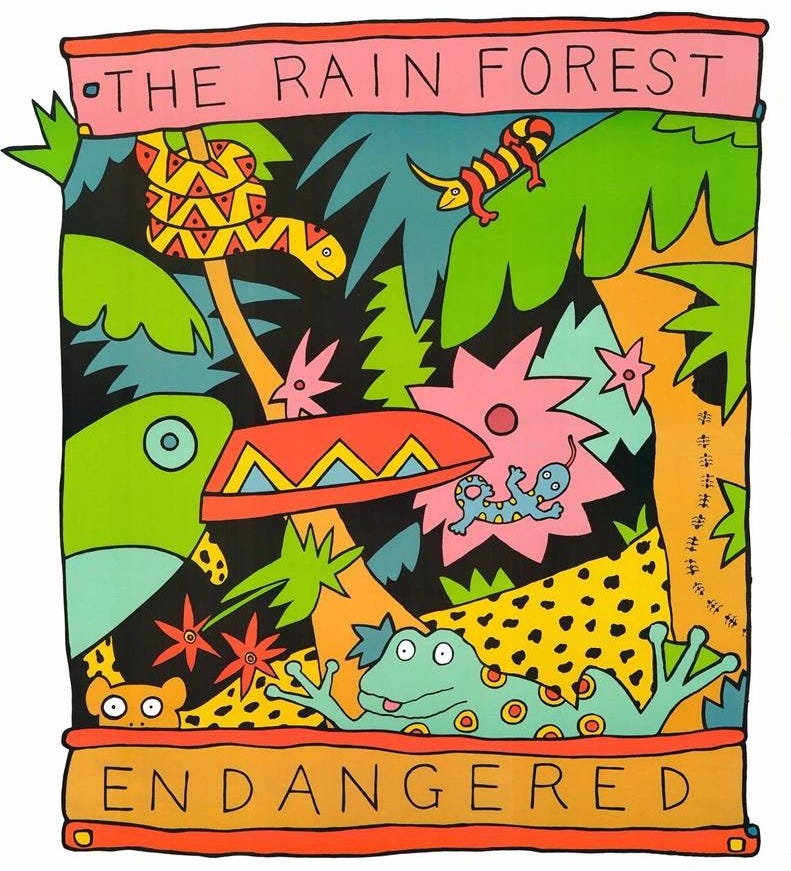

As a kid, I was heartbroken over the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, and I used to stare despondently at the deforestation maps in my Greenpeace or WWF magazines (“Twenty football fields per minute!”). I loved drawing the rainforest, but lacking any real artistic chops, I often used an artwork called “Rainforest, Endangered” as my model—a lush tapestry of brightly colored animals, each having its proper place in a harmonious ecosystem. And then, of course, came the evil humans with their chainsaws, wreaking havoc on this beautiful world!

Little did I know as a kid that a rainforest is a Darwinian inferno of death and suffering, where every creatures is engaged in a fierce competition, and where even the majestic trees only exist because they are locked in a pointless arms race to shoot skyward and steal some sunlight from their competitors. Having never seen a rainforest up close—let alone tried to survive in one—I was free to indulge my childish fantasy of a harmonious whole. That tradition of idyllic portrayals lives on, as in this more recent children’s drawing, where the animals look even more happy-go-lucky than they did in my youth:

Freaks of nature

Now we’re starting to grasp why so many people—especially in modern societies—crave foods that are perceived as “natural” and “uncontaminated.” But is any of our food truly natural? Advocates of organic farming may claim so, but the reality is that all forms of agriculture are extremely recent—evolutionary speaking—and extremely “unnatural”, despite what marketing may suggest. Every acre of cultivated land is dominated by artificial monocultures—usually a single crop or just a handful of varieties—that simply don’t exist in the wild (which is precisely why we had to invent farming in the first place). Plus, nearly all our domesticated plants and animals are genetic freaks, looking nothing like their wild ancestors. And yes, that includes so-called “organic” food.

Take the wild ancestor of corn, for instance, which is called teosinte and not exactly what you’d call popcorn material. Its seeds are encased in tough, hard shells that are a challenge to digest, and the cobs are much smaller than modern corn.

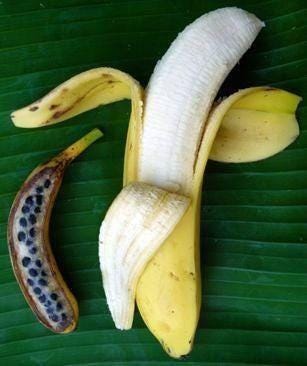

Likewise, the wild ancestor of the banana isn’t the sweet, mushy treat kids adore today; instead, it’s quite bitter and has very little flesh.

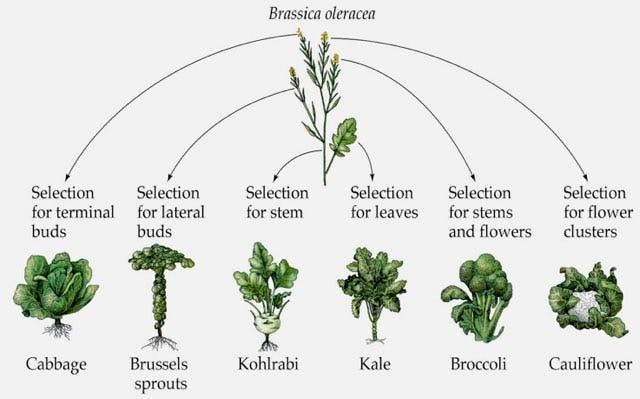

Another fun fact: cabbage, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, kale, broccoli, and cauliflower all belong to the same species—Brassica oleracea—selectively bred into wildly different shapes for standout traits.

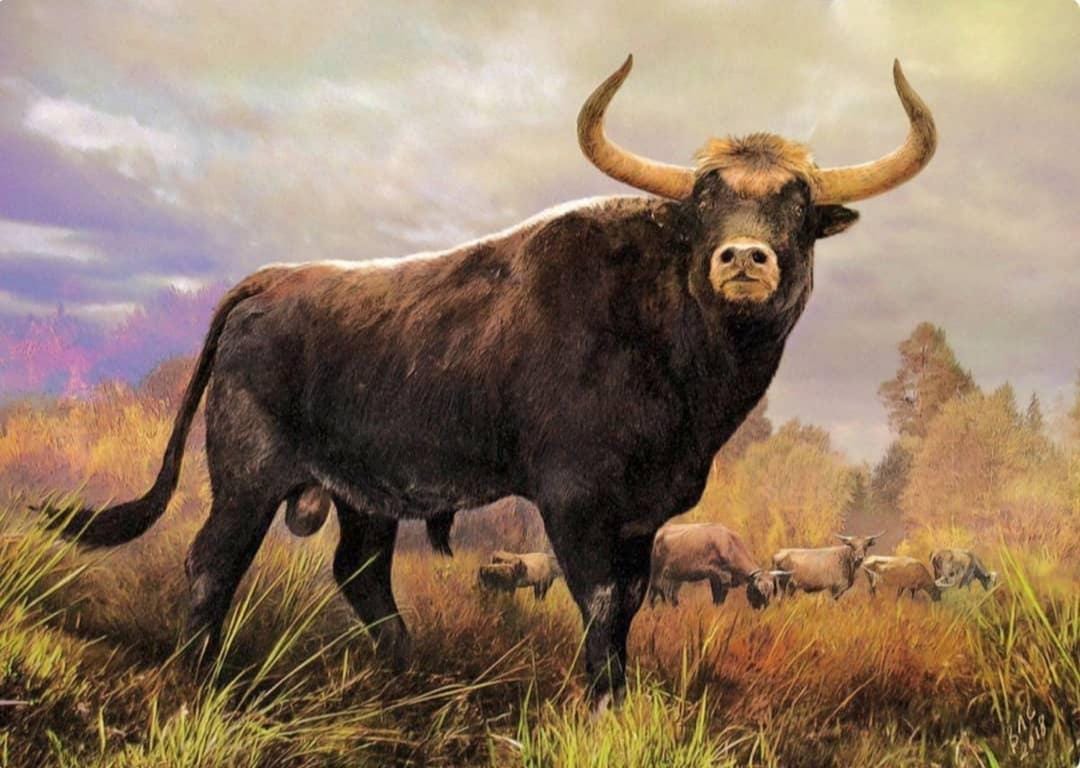

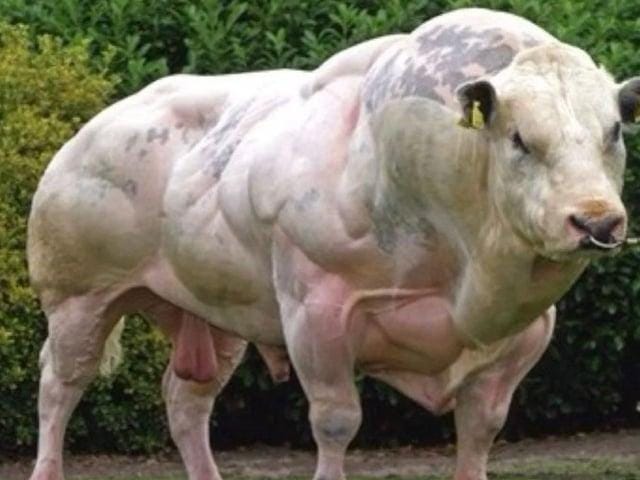

The same goes for our domesticated livestock. Just take a look at the aurochs, the extinct ancestor of all cattle, compared to the striking Belgian Blue cow, known for its unusual double-muscle mutation. Quite the transformation, right?

Agriculture may be the epitome of the unnatural, yet our gut-level faith in “natural harmony” has been artfully grafted onto it. Slap a label like “natural,” “authentic,” or “organic” on food and it’s halfway to public approval, while anything that hints at artificiality is eyed with suspicion. Organic farming, in particular—no synthetic fertilizers, no chemical pesticides, and certainly no genetic modification—is cast as “natural” and therefore inherently good. Despite its relatively small market share, organic enjoys near-universal goodwill. Restaurants and supermarkets never tire of touting “organic” and “100% natural”—claims that are often wobbly—because they know that’s what customers want to hear. Even people who almost never set foot in Whole Foods (because it’s pricey) tend to assume organic is somehow purer and healthier. And it’s not just marketing: Europe’s Green Deal even sets official targets for organic agriculture, aiming to make it at least a quarter of all farmland by 2030. This is despite the fact that organic farming typically has a larger environmental footprint and a worse impact on the climate, along with no verified health benefits for consumers. When it comes to food choices, even Europe—the birthplace of the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment—remains deeply entrenched in irrationality.

So, what does all this mean for the future of our food, particularly meat and dairy? Are we poised to embrace lab-grown meat and farm-free proteins in the near future, or will we hit insurmountable intuitive roadblocks? Stay tuned for the next installment of this essay.

As I am already spoiled by having the fortunate occasion to follow Maarten for many years, this article I may consider as a pearl of wisdom and insight into an amplified trend I notice being propagated all over ( the nature is good hype). Thank you Maarten for this gift of intellectual wisdom. Do I look forward for more ? That's only natural, is it not. 😃

I love this, and am looking forward to part 2.

As you note, it's only well-off people who are very isolated from nature who have the luxury of idolizing nature. In my observations, I also note that this conflation of healthful=pure=natural (and also = local) food is more of an aesthetic than a coherent set of standards. Because it's an aesthetic, violations result in feelings of disgust in a way not possible if it were a a set of reasoned-out premises.

For instance, I live on a small Caribbean island best known for its eco-tourism--hiking through the rainforest, diving on the coral reefs, and that sort of thing. The sort of folks who like to do eco-tourist holidays are also the sort of folks who have feelings about naturalness and purity of food. Also, as previously ranted about, my island is subject to prissy Dutch cultural imperialism, which also has a lot of incoherent eco-puritan ideals.

So for instance, we get tourists who want local* organic foods--but not whelks or breadfruit, which are abundant here but are unfamiliar and (with whelks) honestly pretty weird looking and super chewy--so these things ought to meet the standard, but they're "gross." (*And "local" is time-bound. Breadfruit was imported to the Caribbean from Asia during the golden age of colonialism; it's definitely not native and would probably be considered an "invasive species" by eco-puritans if it were imported to the Caribbean today.) And we get Dutch government consultants who want us to grow more of our own food on the island--but not goat (an "invasive species" per the Dutch but that's also been a food animal here for centuries) and not cassava (also a Caribbean staple, but one that takes significant prep to make non-toxic, which we can't be trusted to do). These things are out-of-place on the Dutch food spectrum, so I think they violate the aesthetic of "pure" food. There's government health advice, too. We are advised to eat organic fruits high in antioxidants, like strawberries and blueberries (which do not grow in the tropics). We are advised to not consume things with a high glycemic index like yams or potatoes (which grow great here).

It's like the ideas about "naturalness" of foods held by our nature-loving tourists and Dutch officials have no awareness that different climates allow different things to grow. There's no awareness of how nature actually works, and how that constrains what foods are locally available. Instead there's an aesthetic of nature, with strict categories that may not be violated, and that are anything but natural.