Back in March, in the basement of a swanky Marriott hotel in Washington, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright had the floor at the Powering Africa Summit, addressing African leaders and entrepreneurs. Trump’s energy czar didn’t mince words: “This government has no desire to come and tell you what you should do with your energy system. It's a paternalistic, postcolonial attitude I just can't stand.” Wright promised that the new administration would engage with African leaders as equals, working together to boost African energy production from any source, including natural gas and coal. “To me it's just blatantly obvious that the world needs more energy, much more energy”. But what about the warming planet? Does Wright believe, as his boss once suggested on Twitter, that it’s all a big hoax cooked up by China? Not exactly. “Climate change is a real issue, but putting it on the same level as human lives, or even above, isn’t something this administration will do.” By the time he wrapped up his speech, Wright was met with a standing ovation.1

If you ask me, this was an embarrassing speech. Not for the man on the podium who delivered it, but for those who should have done so in his stead: Democrats and progressive politicians more generally. You can't blame African leaders for enthusiastically applauding Wright’s words, as he laid bare an inconvenient truth. For decades, Western countries, NGOs, and politicians have indeed been guilty of what can be termed "green colonialism." They've been imposing their wealthy-country preferences and priorities on the global poor through both subtle and not-so-subtle means.

For the record: you don’t need to convince me that Donald Trump is bad news for the world in just about every way. By waging a vindictive war on America’s finest universities and slashing their research funding, he’s engaging in a massive act of self-sabotage and hamstringing American innovation, which will set back global progress on energy innovation by years. By starting reckless trade wars and antagonizing virtually every nation in the world (except the autocracies that offer him private jets), he is disrupting global trade and setting back clean energy. And by letting Elon Musk axe USAID and various other development programs, including life-saving vaccination campaigns, he’s literally condemning thousands to death. DOGE has already caused so much damage to American soft power that leading Kremlin ideologues have been mourning Musk’s exit. And let's not forget Trump’s outright assault on clean energy efforts at home, all in a pointless culture war to own the libs.

And yet: even a broken clock is right twice a day, and it seems Trump’s hour had struck. So why green colonialism? In wealthy countries, fossil fuels are often vilified as an “addiction” that we need to “wean” ourselves from. Not just by radical climate activists, but also by the secretary-general of the UN, by mainstream media, and in prestigious scientific journals like Nature.

But this framing is a serious distortion of reality, which you can only indulge in if you belong to the global 1%. Progress has a way of erasing its own tracks, because solutions are so effective that we tend to forget about the original problems they solved. People in industrialized nations have been ensconced by the comforts of fossil fuels for so long that they’ve become practically invisible to us. We are like the little fish in that David Foster Wallace story who ask, “Water, what the hell is that? Never heard of it.” Fossil fuels are, without exaggeration, the best thing that ever happened to humanity. It’s hardly a coincidence that the precipitous decline in child mortality, extreme poverty and disease all happened in tandem with the industrial revolution. Whether you’re talking about hospitals, sewage systems, water purification plants, vaccination, water pumps—all these marvels of modern technology would be unimaginable without vast amounts of cheap, abundant, and reliable energy. To affluent Westerners, a coal plant might evoke images of toxic smoke and risky greenhouse gases, but for those in poverty, it still symbolizes prosperity and progress, as it once did for us.

Climate change is a real concern, as even Chris Wright admits, but worries about the future of the climate are a luxury reserved for those whose material and social needs are already being met. If you're constantly worried about whether your kids will have enough to eat or if they'll fall ill and you can't cover the doctor bills, then pondering the fate of hypothetical future grandkids isn't in the cards. As you grow richer, your time horizon expands, and you can afford to worry about the distant future and the fate of the planet. The phenomenon of the Green Kuznets Curve bears this out: the relationship between GDP and greenhouse emissions (and other forms of pollution) take the shape of an inverted ‘U’. First, emissions are increasing, because people care about material needs first and foremost, but as people grow richer, they start to care about a clean environment and eventually about the fate of the planet. After that inflection point, emissions start to fall, as people can afford to switch to cleaner energy sources and phase out the dirtiest fossil fuels.

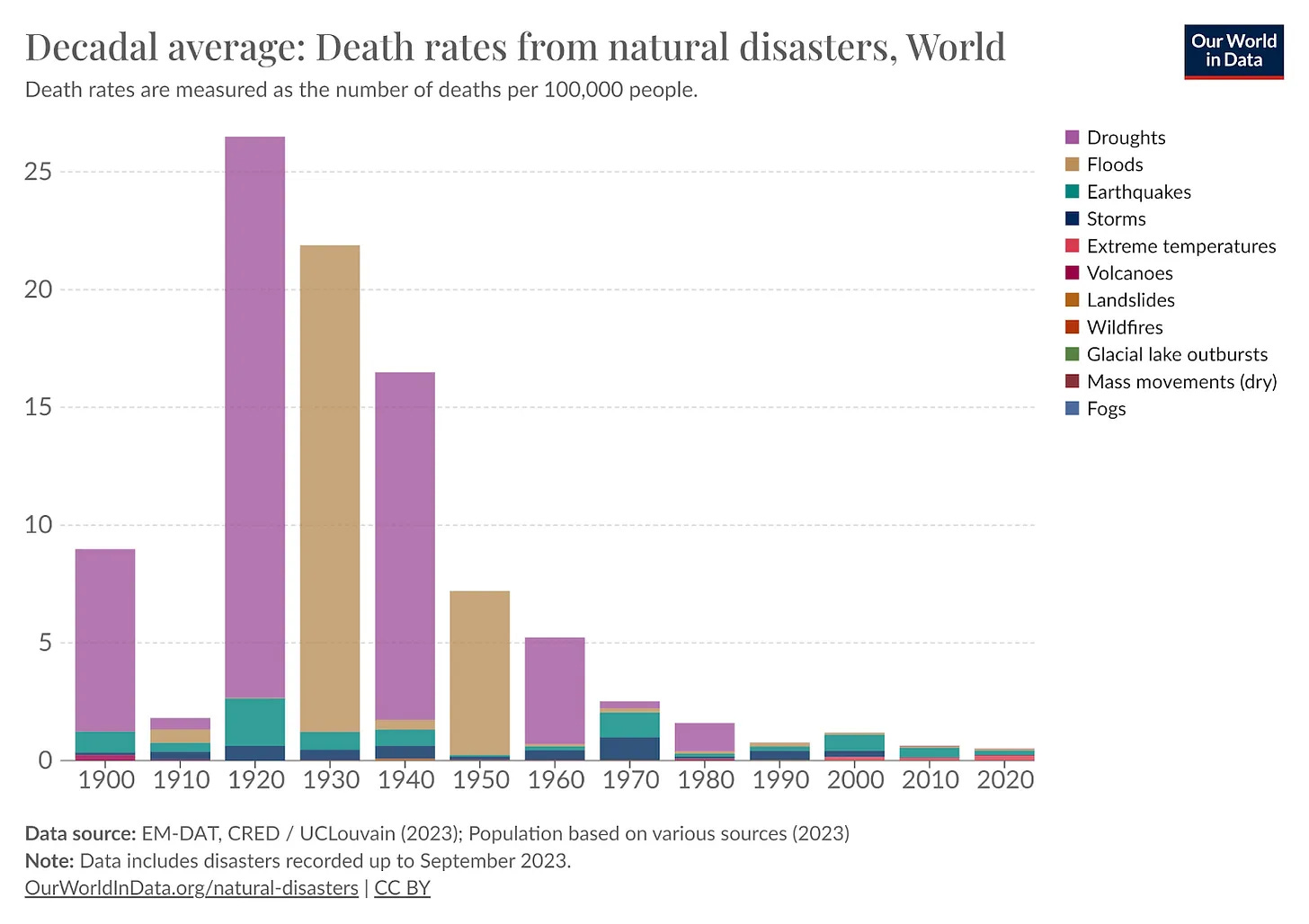

Affluent Westerners, comfortably residing at one end of the inverted U, are now telling people at the other end that they should not start burning fossil fuels. Time and again, they make the same crucial reasoning error. From the fact that poor Africans will be hit hardest by the effects of global warming (correct), they conclude that these people would stand to benefit the most from aggressive emission reductions (utterly wrong). They have forgotten that the best protection against natural disasters—whether man-made or natural—is economic prosperity itself. When it comes to the deadliness of natural disasters, the one factor that overwhelms all the others is not the hurricane’s strength or the heat wave’s temperature, but the income level of the people affected. If you have money, you can build levees, hurricane shelters, sturdy homes, hospitals, air conditioning, and roads with effective evacuation systems.

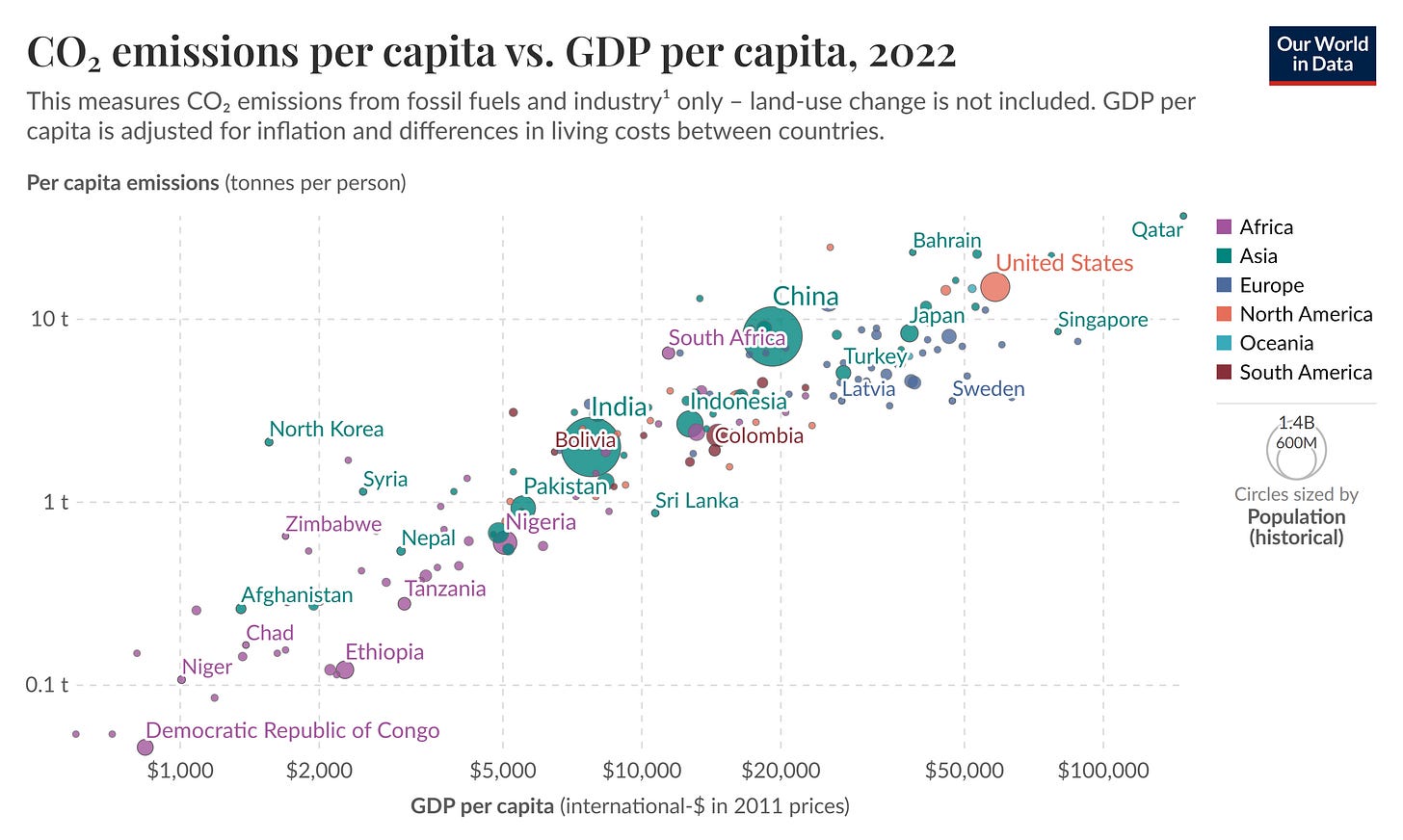

All of this requires tons of steel, cement, glass, aluminum, and a reliable supply of electricity—for which fossil fuels remain indispensable to this day. No country has ever clawed its way out of poverty without hefty doses of coal, gas, and petroleum. That’s why the correlation between GDP and CO₂ emissions per capita remains very strong to this day, and visible at a glance:

How does green colonialism work in practice? Mostly indirectly. Climate activists and NGOs, freaked out by apocalyptic climate scenarios that are not just completely unrealistic but also ignore the massive proven benefits of adaptation, are putting pressure on their politicians to make grand promises to slash emissions. But these politicians aren’t stupid. They’re well aware that fossil fuels are indispensable for sustaining our current levels of prosperity—and if they’re not, reality is ready to deliver a wake-up call. Even the most eco-friendly western leaders couldn’t resist extending licenses for coal plants or launching new gas projects after Russia's invasion of Ukraine (also because they would rather eat their own shoe than keep open a nuclear plant). Now imagine that you are such a political leader in a rich country. You want to flaunt your green virtue, but you also have to keep it real if you want to stay in office. How do you show that you are on the right side of history, without dragging your own country back into poverty? Here’s a tempting thought: what if you just do it at the expense of poor countries?

That’s how we arrive at one of the greatest scandals of our time. Pressured by the climate movement, wealthy Western countries have repeatedly pledged to stop investing in fossil fuels elsewhere (in Africa, where their voters do not live). Back in 2017, the World Bank Group, still largely beholden to Western interests, announced that it would cease financial support for oil and gas extraction, having already phased out coal financing by 2010. Who is most dependent on these loans? The poorest countries, naturally. By failing the global poor, the World Bank Group is shirking its original mandate to combat global poverty and promote economic development. Individual Western countries eagerly take part in this hypocrisy. At the climate conference in Glasgow, twenty rich countries along with the European Investment Bank solemnly pledged to end investments in fossil fuel projects in “overseas territories” by 2025 – how’s that for a nice euphemism?

The winner of the hypocrisy sweepstakes is probably Norway, a nation that rakes in billions every year from its own gas fields while simultaneously lobbying the World Bank to block fossil exploration in developing countries. As a result, the African Development Bank (AfDB) has complained that securing financing for natural gas projects has become incredibly challenging for African nations.

Many climate activists, ostensibly concerned with the plight of the global poor, actively applaud such policies. In good neo-colonialist tradition, they have decided on behalf of poor Africans what is in their best interest. The American climate scientist Michael Mann recently said the quiet part out loud: “We can't let them [poor countries] make the same mistakes we made—our climate can't afford it.” Even Al Gore, hardly a fringe figure in the climate movement, suggested in his book Earth in the Balance that developing countries don’t really need centralized electricity grids like we do, citing economist E. F. Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” philosophy. Surely, a microgrid, a handful of solar panels, and a few batteries should suffice for those people, right?

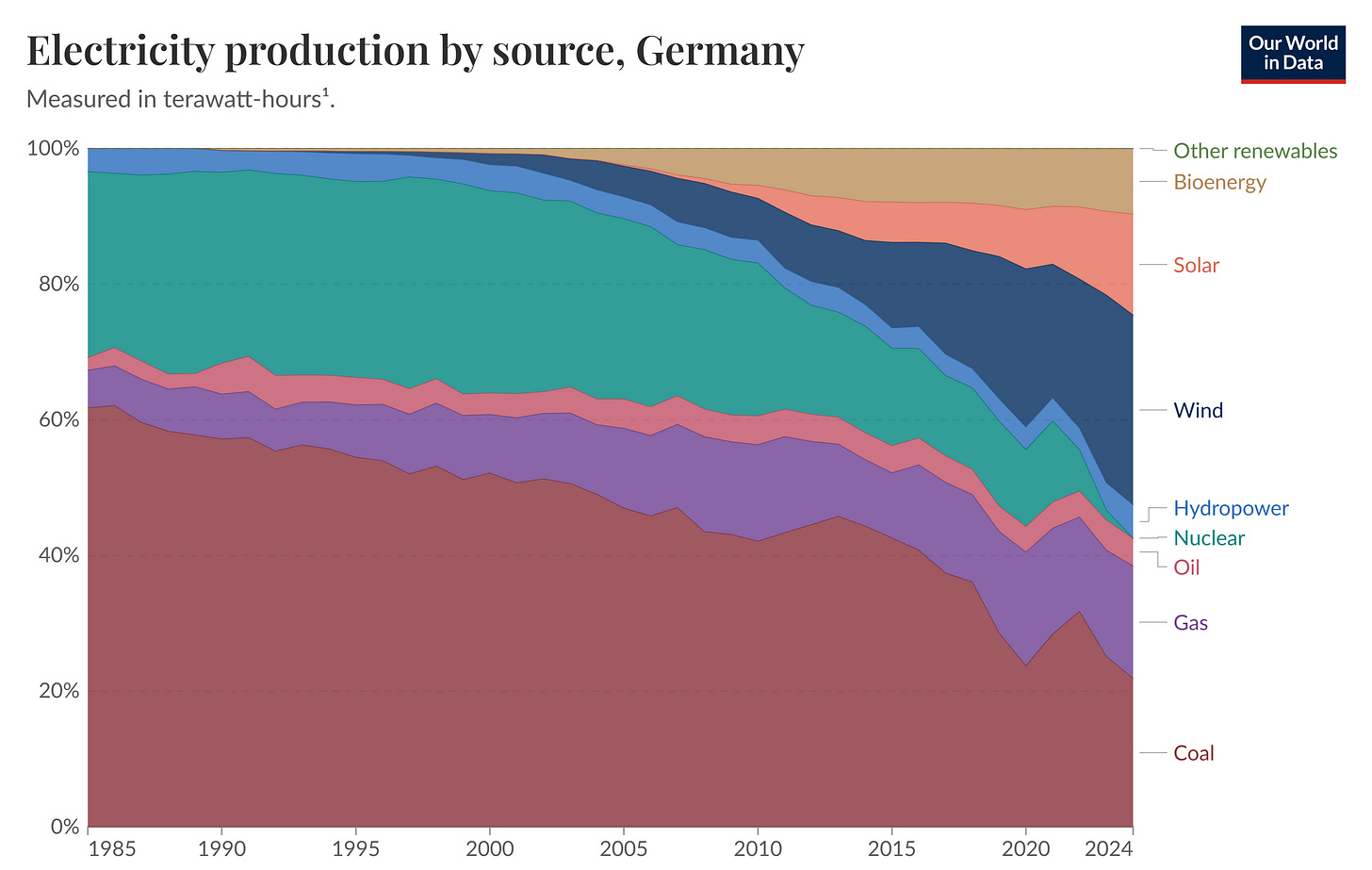

But of course we are already living in sin and so need more fossil fuels, thank you very much. In the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, European countries swooped in and snagged precious natural gas supplies from poorer countries, simply because they had deeper pockets. In countries like Bangladesh, this led to major blackouts and energy rationing. While European nations are lecturing Africans about the benefits of solar and wind, not a single one of them has managed to fully transition its own grids to variable renewables. Even Germany, the self-proclaimed climate champion of the Global north, continues to burn millions of tons of coal annually.

Writing in Foreign Policy, the economist

recently summarized the message that wealthy nations are effectively sending to African countries: “We’ll stay rich, keep you from developing, and send some charity your way as long as you keep your emissions down.” In a piece for the Wall Street Journal, the president of Uganda Yoweri K. Museveni struck a similar note. To prevent African countries from extracting their own fossil riches, while dangling unreliable solar panels and wind turbines in front of their noses, is deeply unjust and a blatant act of neo-colonialism: “Africa cannot sacrifice its future prosperity for Western climate goals.”A particularly jarring example of this colonialist attitude centers on cooking fuels. Indoor air pollution kills 700,000 people every year across Africa, mostly due to smoke from dirty cooking fuels like charcoal, wood or dung. For these people, the switch to clean LPG (Liquified Petroleum Gas) as a substitute fuel is a massive improvement to health—except LPG is a fossil fuel. Having luxuriated in the comforts of electrical power for so long, westerners tend to forget that Africans face starkly different choices. If you already have a clean electric furnace, switching to LPG would indeed be a step backward, but for many Africans it is a huge improvement. By urging African women and children to refrain from using LPG as a cooking fuel, Western institutions like the World Bank are essentially asking them to suffocate from toxic fumes—all to assuage rich people’s fears of the end of the world (see

‘s wonderful book Not the End of the World). The ecomodernist NGO WePlanet just released a delightfully scathing campaign video lambasting this Western hypocrisy.It is maddening that progressives have left such a gift-wrapped opportunity for Trump to exploit. Even those who haven’t actively participated in this climate colonialism have opted to look the other way instead of speaking out—because all these climate activists are well-intentioned, right? All Trump’s envoy had to do to receive a standing ovation from African leaders was to champion energy development regardless of the source, advocate for clean cooking fuels, and denounce the green colonialism of the Western liberal elite. Although WePlanet's recent campaign is a hopeful sign that the tide might be turning, even they are understandably more queasy about coal, which is far more polluting than LPG or natural gas. I recently discussed this with

on an episode of WePlanet’s Bad Ideas podcast, which will be released soon. It is indeed tragic that the very same energy source that is helping to protect humanity against natural disasters is also exacerbating those natural disasters in the long run. Still, I propose the following rule: as long as we in the West have even one coal plant or coal mine on our soil, we should keep our mouths shut about coal investments abroad. In fact, we ought to lend a hand to those countries who wish to tap their fossil resources—after all, we were once in their shoes too.Or here’s an even better idea: if we truly want to stop poorer countries from burning coal and gas without coercing them, we should invent a clean alternative that is just as reliable, weather-independent, affordable, and of course cleaner. Then, let's generously share that technology at no cost. If anyone has the money and resources to make this happen, it's us.

[If you liked this post, hit the little heart or share button, so the inscrutable algorithm will smile upon this Substack.]

Hat tip to

and from the Breakthrough Institute for pointing me to Wright’s remarkable speech in Foreign Policy.

Here's what there is a real shortage of: likes for this post, which deserves all the likes in the universe. Condescending progressive cultural imperialism is such an underappreciated problem, both for human health and long-run for the environment. This "progressive" punishment of developing countries for continuing to use fossil fuels reminds me of earlier efforts to ban effective pesticides like DDT in southeast Asia and Africa, but only after malaria had conveniently been eradicated in Europe and North America. Both also get tied up with flawed Malthusian reasoning about how the environment can't afford for the poors with their high birth rates using resources like developed Westerners do, ignoring the fact that birth rates are down everywhere, including in the developing world, and the key thing that drives birthrates down is that an increase in material well-being leading to more surviving babies. (Of course, declining birth rates is its own problem--but one that Team Climate Apocalypse seems unaware of.)

I will also note that this woke refusal the recognize that the climate concerns of a Malawian mother are different than those of Greta Thunberg basically pushes developing economies into the arms of China, which is much less judgmental about whether one uses cooking gas. Western progressives can have their moral purity in cutting off funding to places that use fossil fuels, but that doesn't mean that China will follow suit. Is that what Western progressives want: the same or more fossil fuel use as there would have been in developing economies, but with the added feature of those economies becoming vassal states of China?

Well-written, but I’d like to add some points of mild disagreement.

- While I agree developing countries have every right to want to develop as quickly as possible, the technologies available to them are also more advanced. I’d be surprised if solar had no role to play in their energy mix.

- The US has an emission profile that’s just not comparable to the rest of the world. If the US had emissions per capita comparable to the rest of the advanced world, the climate crisis would be well on its way to being solved. While not directly related to your point about how the West shouldn’t dictate the energy mix of developing countries, it’s not trivial in a discussion on who gets to lecture who. It feels a lot like they are using Africa to justify their own reliance on fossils, imo inexcusable for a country as rich as the US.

- Action on climate change does pose a coordination problem, if everyone acts in their own self-interest the collective will be worse for it. Usage of fossil fuels cannot just be evaluated in the immediate benefit to people’s lives.