When Progressives Gave Up on Progress

Or why we need a new progress movement

What’s all this buzz about the need for a “progress movement” and a new field called “progress studies”? Don’t we already have progressives—what’s in a name—to take care of that? If only it were that simple!

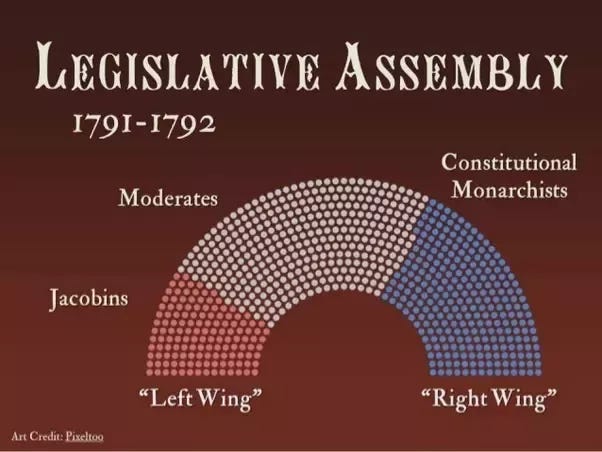

As you might know, the original divide between Left and Right, between progressives and conservatives, traces back to the French Revolution. In the French National Assembly, advocates of the Revolution and the Enlightenment ideals happened to be seated on the left side of the president, while defenders of the ancient régime and the privileges of the aristocracy occupied the right side.

At its core, being on the Left meant championing the Enlightenment belief that misery is not inevitable, that we can make a better world for everyone if we put our minds to it. Leftists wanted to liberate humanity from the shackles of dogma and tradition, striving towards a new society based on individual freedom, equality and human dignity. Some leftists pushed for revolutionary upheaval, while others preferred gradual reform. Being on the Right, by contrast, meant defending traditional hierarchies and institutions against upheaval, especially of the radical kind. The reactionary wing of the Right dreamt of reverting society to its pre-Enlightenment state, while the moderates supported only slow, cautious changes and were wary of untested radical ideas.

A bizarre reversal

Does that distinction still hold up today? Of course, we should not expect our current left-right divide to simply map onto the seating of the French parliament two and a half centuries ago. Plenty of water has passed under the bridge since then, and political scientists have devised more sophisticated ways to distinguish political identities. There is also plenty of ideological diversity within each camp. I recommend

’s insightful recent post about the evolution of the left-right divide over time:And yet, in a number of respects, the political opposition between Right and Left has been almost flipped on its head. Many self-proclaimed progressives seem to have turned sour on core tenets of the Enlightenment, and even on the whole idea of progress. Defenders of degrowth and post-growth argue that economic growth is a harmful fetish, that we have become too prosperous, and that industrial modernity is exploitative and ruining our planet. Even more moderate leftists claim that globalised capitalism is an oppressive system that keeps widening the gap between rich and poor (in fact, we have seen a spectacular decline in poverty and inequality). Free speech, once a progressive cause, has been discredited by critical race theorists as nothing more than a cynical ploy of the powerful to dominate the weak. And the Enlightenment project itself? That was always just a fig leaf for cultural supremacy and colonialism.

Meanwhile, many political conservatives have gradually warmed to many core values of the Enlightenment (after having fiercely opposed them for generations). There's a long list of progressive ideas that were once seen as radical but have become so mainstream that virtually every political conservative has come to accept them: universal suffrage, interracial marriage, gender equality, separation of church and state, gay rights, free speech and the right to blasphemy. Even during Trump's first term, Republicans kept slowly but surely shifting leftward on issues of race and sexuality.

Many conservatives now proudly champion the moral and technological progress our societies have made over the past century. Sometimes their support remains reluctant and lukewarm, but in other cases, such as gay rights, conservatives have completely come around to radical notions they once abhorred. In Europe, this shift is closely tied to the context of mass migration. In the case of Far Right parties such as the French Rassemblement National, this newfound support for gay rights feels disingenuous, more a cudgel to beat Muslim immigrants. However, moderate conservatives seem genuinely supportive. Right now in Europe, if you're looking for allies to protect gay rights against religious intolerance, moderate conservatives are a more dependable choice over progressives. This creates a self-reinforcing dynamic: the more conservatives proudly champion “our” enlightened Western values, the more progressives grow wary.

All of this has led to some strange inversions. If you hear a politician in Europe singing the praises of the Enlightenment and championing human ingenuity as a solution to our problems, chances are that they identify as "conservative." By contrast, if you hear an intellectual scoffing at the Enlightenment, railing against economic growth as a dangerous fetish, and warning against the false allure of techno-fixes, they’re likely to identify as “progressive”.

Things get even more bizarre when progressives shy away from claiming credit for their own victories. If you listen to some progressives today, they’ll tell you that racism and sexism are so deeply ingrained in our societies that any perception of moral progress is illusory. At best, they argue, overt forms of oppression have merely morphed into subtler, systemic, and structural ones, which might be even more insidious. Some progressives even flatly deny that poverty has declined. As Steven Pinker once quipped: “Intellectuals hate progress. Intellectuals who call themselves ‘progressive’ really hate progress.”

So, how did we find ourselves in this topsy-turvy world where conservatives are (almost) better champions of progress and Enlightenment ideals than self-proclaimed progressives? That's the puzzle I unravel in my latest book, Het verraad aan de verlichting (The Betrayal of the Enlightenment), which hit the shelves in Dutch this Spring. As I see it, three major ideological currents in progressive thought contributed to this shocking reversal. The first one is postmodernism, which turned the weapons of the Enlightenment against itself and undermined the belief in objective truth, rationality and moral progress. Next comes the rise of victim-versus-oppressor binaries which—together with the hangover from Western colonialism—ended up indicting Western civilization as the root of all evil, including everything this civilization has brought forth. Lastly, there’s the rise of progressive environmentalism, which is highly suspicious of modern technology and the growth paradigm. While originally a right-wing affair of blue-blooded aristocrats, environmentalism almost completely switched sides somewhere around the 1970s.

Why I’m still a progressive

At my book launch in Antwerp, I delved into these topics during a lively debate with Bart De Wever, the long-standing president of Flanders' major conservative party who is now also the Belgian prime minister. The central bone of contention: if many progressives have indeed turned their backs on Enlightenment values—material prosperity, technological innovation, free speech, secularism—should conservatives step in to carry the torch in their stead? It was a spirited yet constructive exchange, which you can watch here (if you don’t speak Dutch, YouTube's auto-translate might help you out).

As a progressive, of course I applaud moderate conservatives like De Wever for advocating Enlightenment values—after all, the Enlightenment could use all the allies it can get! Yet, debating De Wever served as a reminder of why, despite my frustrations with many of my fellow progressives and despite De Wever's playful challenge to switch allegiances ("Just say the words: I, Maarten Boudry, am a right-wing twit"), I remain a progressive at heart.

Right after my debate with De Wever, I recommended that he check out Friedrich Hayek’s brilliant essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative", knowing that he has a fondness for economic liberalism and counts Margaret Thatcher among his political heroes. That must have struck a chord, as De Wever later delivered a speech (in English) for the centre-right International Democracy Union, in which he reflected on our debate and tackled Hayek's arguments.

The problem with conservatism

One problem with conservatism, as Hayek identified it, is that it’s an aimless ideology without a clear vision. In fact, it has the curious tendency to blend into its surroundings, like a chameleon slowly but reluctantly changing colors. Consequently, conservatism can mean quite different things depending on where you live. In Western Europe, conservatives increasingly align with free-market liberalism and Enlightenment values, because that has become our European tradition. Meanwhile, in formerly communist countries, conservatives tend to favor centralized government, collectivism, and wealth redistribution—that, after all, represents the “tradition” in those regions. This adaptability also explains how conservatives sometimes end up embracing ideas their intellectual forebears fiercely opposed.

Still, that leaves conservatives adrift, lacking a clear direction. What is the next moral revolution looming on the horizon? Will conservatives once again resist the novel ideas and technologies, only to belatedly concede that the radicals were right all along? Conservatives are great at safeguarding past achievements, but without progressive forces to drag them along, they have no idea where to head next—and indeed, they’d much rather stay put. As Hayek wrote:

“It has […] invariably been the fate of conservatism to be dragged along a path not of its own choosing. The tug of war between conservatives and progressives can only affect the speed, not the direction, of contemporary developments. But, though there is a need for a "brake on the vehicle of progress," I personally cannot be content with simply helping to apply the brake. What the liberal must ask, first of all, is not how fast or how far we should move, but where we should move.”

In his battle against the allure of collectivism and central planning, the liberal Hayek often found himself in alliance with political conservatives who were defending the time-honored Anglo-Saxon traditions of economic liberalism and free trade. Yet, Hayek insisted that liberalism is anything but a conservative ideology. Markets, after all, are disruptive and destabilizing forces that drive constant change. As the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter noted, innovation can only emerge through creative destruction—the relentless upheaval of established industries and conventional practices.

Like Hayek, I believe in boundless growth, experimentation and innovation. Plus, I’m also impatient (probably more so than Hayek). I’m eager to shake things up and drive change —there’s just too much avoidable suffering and oppression in the world that we can’t ignore.

Cultural chauvinism

Another problem with conservatives as the torch-bearer of the Enlightenment is the inherent tension with one of its fundamental principles: universalism. De Wever stands up for the Enlightenment mostly because he believes it is part of "our" European heritage, and because it organically grew out of the fertile soil of Christianity. This story, though very fashionable these days, is wrongheaded. In reality, the Catholic Church and other Christian authorities fought the Enlightenment tooth and nail, and it took roughly two centuries for them to finally admit defeat and come around to liberal democracy and secularism. Almost all major thinkers of the Enlightenment ended up on the Index of Forbidden Books, facing resistance from both Catholics and Protestants against secularism, democracy, freedom of thought, and against scientific advancements such as heliocentrism, the germ theory of disease and evolution.

Moreover, if Christianity is the bird that incubated the egg of the Enlightenment, then why did it take nearly 2,000 years to hatch? From the belief that the Enlightenment is a progeny of Christianity, it’s only a short step to the chauvinist notion that other cultures are simply inhospitable to the Enlightenment. But if the Enlightenment stood for anything, it was for universalism—science, freedom, and democracy belonged to all of humanity, not just to one religion or tribe. Reclaiming the Enlightenment for Europe risks turning these universalist principles into something akin to cultural property.

This does not mean that conservatives like Bart De Wever are my enemy. In my book, I argue that progressives and conservatives actually need each other. Without conservatives occasionally hitting the brakes, progressives tend to move too fast and break things. But without progressives dreaming up bold new futures, nothing would ever change.

As for me, I’ll keep on pushing for a radically better world, and I’m proud to be a member of the burgeoning progress movement. Stay tuned for the translation of my book!

Interesting article, and I am impressed that you had a pubic debate with the Prime Minister of Belgium!

Great post, Maarten!